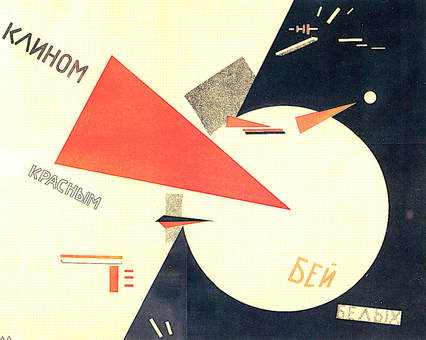

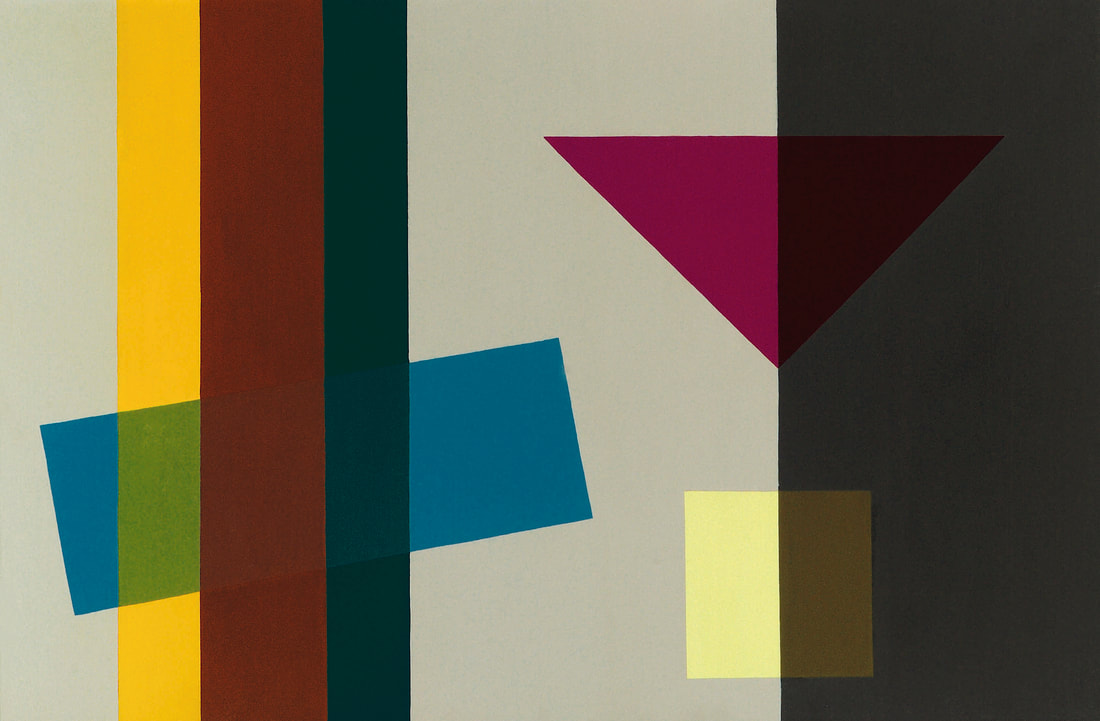

Art and Revolution The Bolshevik revolution of 1917 was one of the most momentous events of the 20th century. It reshaped almost every aspect of our lives – politically, socially and culturally – and now, exactly a hundred years later, we can pause and examine its heritage. In Europe, the Royal Academy held its blockbuster exhibition Revolution: Russian art 1917-1932, the British Library its Russian Revolution: Hope, Tragedy, Myths show, Deutsches Historisches Museum in Berlin mounted its major 1917: Revolution: Russia and Europe exhibition and there is a plethora of exhibitions around the world including The Museum of Modern Art’s landmark exhibition A Revolutionary Impulse: The rise of the Russian avant-garde in New York. In Australia cultural celebrations of the Russian revolution are more muted with an exhibition of Russian revolutionary graphics opening at the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra in late August, drawing on its internationally significant holdings of Russian avant-garde art, and a big exhibition Call of the avant-garde: Constructivism and Australian art at the Heide Museum of Modern Art in Melbourne. Constructivism was the art movement of the Bolshevik revolution, whose ideology reflected that of the fledgling socialist state, and whose forms swept into every aspect of cultural production including typography, book design, poster art, architecture, furniture, ceramics, textiles, theatre stage sets, cinematography, music, poetry as well as painting, sculpture and printmaking. For example, when the new Soviet state exhibited at the Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes in Paris in 1925 the Soviet Pavilion was designed by the constructivist architect Konstantin Melnikov, while for the interior Aleksandr Rodchenko designed a constructivist workers’ club. Constructivism was at the service of the revolution and the Soviet state, so that El Lissitzky’s famous lithographic poster, Drive the red wedge into the whites, 1920, commissioned by the Political Department of the Western Front, in many ways sums up the essence and principles of constructivism. If we examine this civil war image – the graphic elements are simple and geometric in character. The black and white trapezoidal areas are obliquely separated. A sharp aggressive red triangle – symbolic of the red army, literally deflowers the broken white circle (the tsarist army) – the simple sans serif lettering, obliquely placed in relation to the total geometry of the poster – reads "with the red wedge, destroy the whites" i.e. the Bolshevik army drives the red wedge into the ranks of the whites (also in Russian there is an alliterative quality in the words). Although economically the young Soviet state was a basket case with sanctions and economic blockade imposed by the surrounding imperialist powers, culturally it was a superpower and constructivism was a subversive export designed to spread the Communist revolution to the rest of the world. Soviet constructivist artists and their fellow travellers infiltrated the revolutionary Bauhaus in Germany and before long Kurt Schwitters and Laszlo Moholy-Nagy converted to Constructivism mainly through contact with El Lissitzky. Moholy-Nagy wrote in 1922 in his article ‘Constructivism and the Proletariat’: "Everyone is equal before the machine. I can use it, so can you ... There is no tradition in technology, no class consciousness. Everybody can be both the machine's master and its slave. This is the root of Socialism ... This is our century: technology, machine, Socialism ... The art of our time has to be functional, precise, all-inclusive. It is the art of Constructivism ... In Constructivism form and content are one ... Constructivism ... is not confined to the picture frame and pedestal. It expands into industry and architecture, into objects and relationships. Constructivism is the Socialism of vision." Constructivism and its socialist ideology were inseparable and every constructivist, to the woman – as many prominent Constructivist artists were women, including Lubov Popova, Varvara Stepanova, Olga Rozanova and Alexandra Ekster – felt that they were part of a global revolution. One difficulty with an exhibition such as the Call of the avant-garde is that most of the Australians were quick to copy the outside forms of Constructivism, but not the ideological content. The great Soviet poet and Constructivist artist and designer Vladimir Mayakovsky was to term such endeavours as “carrot coffee”, a reference to those who captured the outside form, but failed to understand the essence. The Heide exhibition includes a small handful of Russian works, the Rodchenko painting and photograph on loan from the Art Gallery of New South Wales and the El Lissitzky Proun lithographs from the Art Gallery of Western Australia are the most remarkable of these. There are also a few superb pieces by Erich Buchholz, a German artist who spent most of his life denying that he was a Constructivist, but came closest to them in spirit and ideology. The rest of the show consists largely of Australian and British artists, of a much later generation, who responded to some of the forms and ideas of Constructivism. Sally Smart made her own complex and multifaceted ‘Constructivist puppets’ that engage on a number of planes with ideas of Russian feminists, while Justene Williams recreates costumes for Victory over the sun (1913), the Russian Futurist opera written in a transrational language that celebrated the emergence of a number of Constructivist elements. Ralph Balson, Frank and Margel Hinder, George Johnson and John Nixon in their art, in different ways, celebrate Constructivist forms. The exhibition curators, Sue Cramer and Lesley Harding, adopt a broad-brush definition of Constructivism, so that Inge King, Victor Pasmore, Anthony Caro, Gunter Christmann, Emily Floyd, Meredith Turnbull, Max Dupain, Olive Cotton, Melinda Harper and Raafat Ishak all somehow fit under the Constructivist banner. Vladimir Lenin and his enlightened Commissar for Education and Culture Anatoly Lunacharsky may not have personally liked or understood Constructivism, but were happy to tolerate artistic diversity. Some of the subsequent Soviet leaders were incapable of accepting anything other than academic realism. Constructivism never died in the Soviet Union, seeking refuge in typography, filmmaking, photomontage and poster art, but it did take root in the West and ultimately permeated many aspects of art and design.

2 Comments

Lansheng Zhang

17/7/2017 16:40:03

What a great term of "carrot coffee"!

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

GRISHIN'S ART BLOG

Sasha Grishin AM, FAHA is the author of more than 25 books on art, including Australian Art: A History, and has served as the art critic for The Canberra Times for forty years. He is an Emeritus Professor at the Australian National University, Canberra; Guest Curator at the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne; and Honorary Principal Fellow, Faculty of Arts, at the University of Melbourne. Archives

September 2023

Categories

Keep up-to-date with Sasha Grishin's blog with the RSS feed.

RSS offers ease of access and ensures your privacy, as you do not need to subscribe with an email address. Click here to download a free feed reader |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed