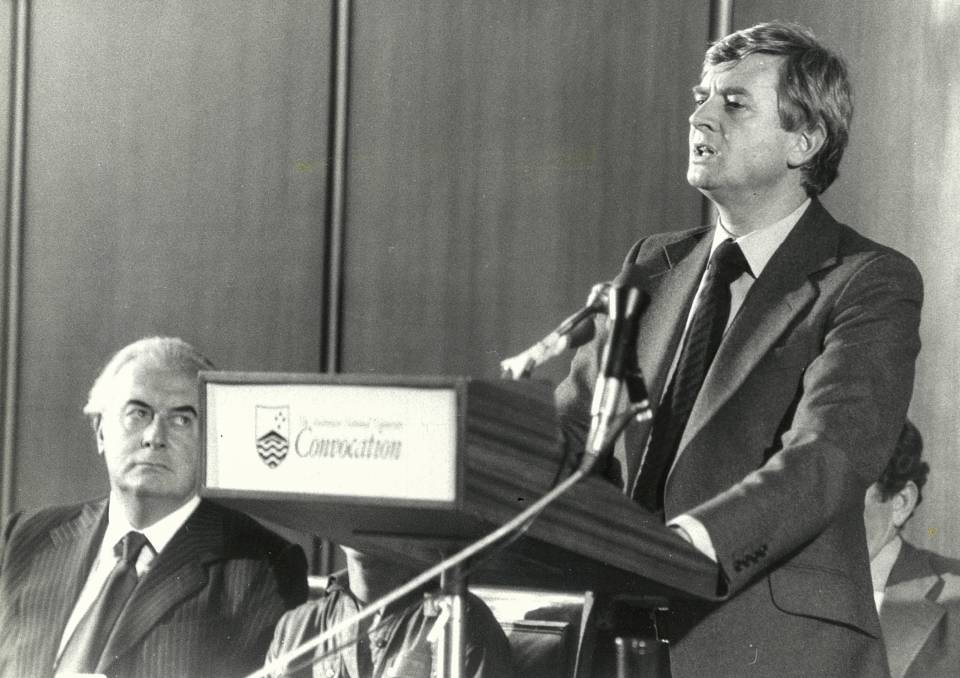

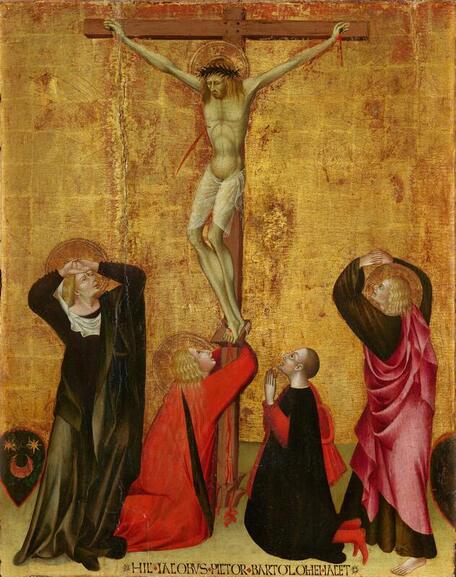

James Mollison – a legacy James Mollison – Australia’s premier art director, charismatic visionary and my friend, died 19 January 2020. He was 88 years old. Who was James Mollison – a gay lad from Wonthaggi in South Gippsland in Victoria, who trained as a schoolteacher and as the arts teacher at Melbourne High inspired the young Les Kossatz to become an artist. He subsequently became an education officer at the National Gallery of Victoria, briefly was the director of Melbourne’s Gallery A commercial art gallery and in 1967 was the director of the Art Gallery of Ballarat, then known as the Ballarat Fine Art Gallery. At the age of 38, in 1969, he came to Canberra where he stayed for 20 years and from obscurity rose to become a household name in the Australian art world and well known in the community more broadly. He initially took up the position of the executive officer for the Commonwealth Art Advisory Board and as the exhibitions officer in the Commonwealth Prime Minister's Department. Two years later, his position had morphed into that of the acting director of the fledgling Australian National Gallery and by 1977 Mollison was appointed as the director of the gallery, a post that he retained until 1989, when he returned to his beloved Melbourne. From 1990 to 1995 he served as the director of the National Gallery of Victoria. In 1977, when Mollison was appointed as gallery director, I was tasked with establishing the academic discipline of art history at the Australian National University. What appealed to me was to work, where possible, directly from the art object (rather than from reproductions) and the fledgling national gallery seem to present an ideal opportunity. The only fly in the ointment was that the gallery was not yet built and was not to open to the public for another five years. When I discussed this with the director, he was unfazed and simply told me to bring my students to the warehouse in the slightly seedy Canberra suburb of Fyshwick where the collection was housed. So commenced a relationship that continued for many decades. As well as heading the art history discipline at the university, I was also the art critic for The Canberra Times, a curator and several other things. I collaborated with Mollison on many projects and got to know him quite well professionally and socially. He was a passionate workaholic, encyclopaedic in his art interests, he had a wonderful eye and an unquenchable enthusiasm. Although he was best remembered for several spectacular purchases, such as Jackson Pollock’s Blue poles (1952) and Willem de Kooning’s Woman V (1952-53), when he worked with our visionary Prime Minister Gough Whitlam, these were minor skirmishes with philistine politicians and their friends in the gutter media of the day. The attacks drew blood, Whitlam lost the election and two major potential acquisitions, Georges Braque’s Nu Debut (1907) and a fourth century BC life-size bronze, possibly by Lyssipos, were forfeited. Mollison’s acquisitions stood the test of time and have increased in value some 300 fold. Mollison did manage scores of major acquisitions, including Kazimir Malevich’s House under construction (c1915-16), Claude Monet’s Grainstacks, midday (1890), Constantin Brancusi’s Birds in space (1931-36) and Amedeo Modigliani’s Standing nude (c.1912). I will never forget my first encounter with some of the newly acquired gems for the collection first shown in the exhibition Genesis of a Gallery held at the ANU, incidentally, directly beneath my office. Fred Williams came to my office to whisk me away for an unofficial preview before the opening. It was then that I was first introduced to the Ambum Stone, one of the most perfect sculptures that I have ever experienced. Williams and Mollison shared this opinion. The gallery collection is studded with these outstanding aesthetic objects. Mollison, like a librarian in love with books, loved art and bought widely and bought well. By the time the gallery opened to the public in 1982, it had a collection approaching 50,000 art objects, while by 1998, this had jumped to over 90,000 art works. Not only did he secure (with love) from Sunday Reed Nolan’s Kelly series and Arthur Boyd’s huge gift to the nation, he also co-funded and acquired the Aboriginal Memorial (1987). The Ken Tyler print collection, Picasso’s Vollard suite and the huge collection of Ballets Russes costumes, stage sets, Russian graphics, constructivist and futurist art also entered the collection. Mollison was a driven visionary, hired some of the best curators nationally and internationally (despite their idiosyncrasies and difficult personality traits) and trained a whole new generation of art professionals (many of whom were my former students). I would argue that he largely created a new breed, for Australia, of art professionals that went through the entire system. What was the legacy of Mollison? He re-booted the Australian museum scene, helping to destroy our provincialism and to bring it out on to the international stage. Ultimately, he, more than any other individual, changed the way most Australians view art today in their public galleries and museums. We have an enormous debt to this very unusual individual and it is a strange feeling that he is no longer with us.

1 Comment

|

GRISHIN'S ART BLOG

Sasha Grishin AM, FAHA is the author of more than 25 books on art, including Australian Art: A History, and has served as the art critic for The Canberra Times for forty years. He is an Emeritus Professor at the Australian National University, Canberra; Guest Curator at the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne; and Honorary Principal Fellow, Faculty of Arts, at the University of Melbourne. Archives

June 2024

Categories

Keep up-to-date with Sasha Grishin's blog with the RSS feed.

RSS offers ease of access and ensures your privacy, as you do not need to subscribe with an email address. Click here to download a free feed reader |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed