2016 in review Is it only me, or has 2016 indeed been a particularly difficult and bleak year full of shocks and body blows? It was the year when ‘post-truth’ was deemed by the Oxford dictionaries as their ‘word of the year’, when Donald Trump was elected as president of the United States of America, when Brexit became a word as Britain prepares to leave the European Union and the Turnbull government was returned to office, albeit with the narrowest of margins. It was a year when racism and xenophobia came to be seen as mainstream; anti-Semitism, Russophobia and Islamophobia have become the accepted small change of gutter politics, and the act of crossing from one country to another to escape persecution was deemed a crime to be punished by banishment for life. On a personal level, the black angels of death have hovered over my life with the death of my beautiful friend and brother, Vladimir, followed by the loss of friends and luminaries in the art world, including Dorothy Herel, Warwick Reeder, Paul Cox, Robert Foster, Inge King, Colin Holden, Jenie Thomas and Leonard Cohen. It has been a year when arts in general and the visual arts in particular have suffered crippling cuts perpetrated by the Turnbull-Abbott government. The raid on the budget of the Australia Council by George Brandis, when he was arts minister, has largely remained in place under his successor Minister Mitch Fifield. The discretionary funding for small grants and innovative programs of Oz Co has been largely wiped out and as a direct result many thousands of artists have lost their meagre subsidies and have had to stop making art. The arts are bleeding in Australia with poorer than average sales in commercial art galleries, and the dumping of art this year on the secondary market due to ill-considered federal government legislation on retirement collections has impacted negatively on the value of many artists’ work. In the meantime, the same federal government has taken a razor to our major national cultural institutions and slashed the budgets of the National Gallery of Australia, National Library of Australia and other institutions charged with preserving our cultural heritage. It is only now, at the end of the year, that the full extent of the savagery is being felt, as staff are offered their voluntary redundancies, others are losing their jobs and crucial appointments are not being filled. The nationally significantly research tool used by most people working in the humanities in Australia, Trove, is under serious threat, while other institutions are revising opening hours, schedule of exhibitions and are axing services. Only the Australian War Memorial, with former Liberal Party minister Brendon Nelson at its helm, seems immune to the cuts. This year has also been the year when Australian art schools have increasingly felt like a threatened species. Personally, I think that the rot set in when art schools were forced into mergers with universities and, unless they were big enough, rich enough and autonomous enough to maintain a strong independent identity, they became schools within universities and subject to cuts and rules that make little sense to an art school. The poorly thought through plan to merge the Sydney art schools into a single unhappy family died a quick death, but the stink remains. The future of the Sydney College of the Arts is in doubt, the College of Fine Arts at the University of NSW has changed its name, signalling a change in purpose and orientation with a silly acronym, UNSWCOFAD, in place of the well established brand name COFA. The National Art School, Sydney’s oldest and most respected art school, is also facing an uncertain economic future. Even the ANU School of Art is rebranding and putting design into its name. Sorry the acronyn ANU SAD is the kiss of death. In the real world, rebranding automatically means a loss of market share and firms that are forced to rebrand dedicate huge budgets to sell their new identity. So, should one reach for a rusty razor and slit one’s wrists when reviewing the past twelve months in the visual arts in Australia?

The answer is a categorical no and the reason for that is the calibre of the art created by Australian artists in 2016 has been outstanding. Also, exhibitions staged by public and commercial art galleries and museums have generally been memorable, professionally presented and of a high aesthetic and intellectual level. Despite the deliberate financial cuts and the bleak conditions created by our politicians, there is resilience amongst Australian artists and the need to create art is a necessity and not a decision taken on sound fiscal grounds. Images from Vivid in Sydney in 2016, and the exhibition at the Art Gallery of NSW Julian Rosefeldt's Manifesto, 2014-15 with Cate Blanchett playing all of the roles.

2 Comments

Our heritage under threat Many years ago, I was working in Cappadocia in central Anatolia in Turkey on the early Christian and medieval Byzantine subterranean churches. Cappadocia is a site of enormous cultural and historical significance that not only carries the traces of several civilisations – Roman, Byzantine, Seljuk and Ottoman – it is also a place of great and unusual scenic beauty. Cappadocia lies at the heart of Byzantine monasticism. It is the legendary birthplace of numerous saints including St George; the place of martyrdom of St Longinus, the centurion who stood at the foot of Christ's cross; the birth place of some of the finest theologians of the Christian church, including St Gregory of Nazianzus and St Gregory of Nyssa; and the birth place of St Basil, the Father of Eastern monasticism and the author of one of the main liturgies of the Church. Within about 120 square kilometres lie the remains of about one thousand Byzantine churches, monasteries and secular buildings hewn out of the soft volcanic rock. One of the biggest threats to Byzantine Cappadocia was from vandalism, where local children would throw rocks at the painted images; their parents converted the churches into pigeon houses to collect the bird droppings as fertiliser for their crops, while others used them for cold storage for perishables, especially citrus crops. The major problem was that the locals saw the Byzantine churches as remains from an alien and even hostile culture, and I saw my role and that of my colleagues as to teach people that it was also their culture and their heritage. The locals did come on board and the place received World Heritage Listing and now this once-impoverished community sits on a goldmine of cultural tourism. The sites are zealously protected by the locals, and governments at all levels are involved in their conservation. Earlier this year I travelled for the first time to the Burrup Peninsula, which is part of the Dampier Archipelago that lies about 1200 kilometres north of Perth and reaches out into the Indian Ocean off West Australia’s Pilbara coast. The Burrup Peninsula (known in the local language as Murujuga – meaning ‘hip-bone sticking up’) contains the world’s richest collection of petroglyphs (images incised into stone). Archaeologists estimate about one million petroglyphs in the area and most of these date from about 40,000 BP through to 5,000 BP, although there are some from more recent times. In other words, they predate ancient Egyptian art by thousands of years and are older than most of the rock art of Europe. It is a place of great spiritual significance and beauty. It is certainly one of the most important centres for Australian art in the world and a key centre for rock art internationally. Sadly, not only is the Burrup Peninsula not on the World Heritage Register, but it is being vandalised by the Western Australian State Liberal Party government with Premier Colin Barnett at its head by allowing industry into this pristine environment. It is, however, on the National Trust of Australia Endangered Places Register and we have competing estimates on the number of petroglyphs already destroyed and the number currently under threat. On the Burrup Peninsula two tragic circumstances have converged. One is that it is the site of extensive industrialisation – both a huge gas plant and now an expanding fertiliser plant run by the international company Yara Pilbara – with acid rain falling on the ancient art. The second is that the site is regarded as of significance for Aboriginal culture. Of course it is but, much more than this, it is an immense cultural treasure house for all Australians. The short-sighted short-term gain from mineral exploitation comes at the expense of permanent long-term destruction of an asset that will bring billions of dollars in future cultural tourism. Sadly, while our culture is being destroyed, the Turnbull Federal Coalition government is too concerned with appeasing its friends in the West to stand up and protect Australian art. The evidence that Australia’s ancient culture has been destroyed in a wholesale manner and that this is an ongoing tragedy is irrefutable, although there can be an argument over the degree and rate of destruction.

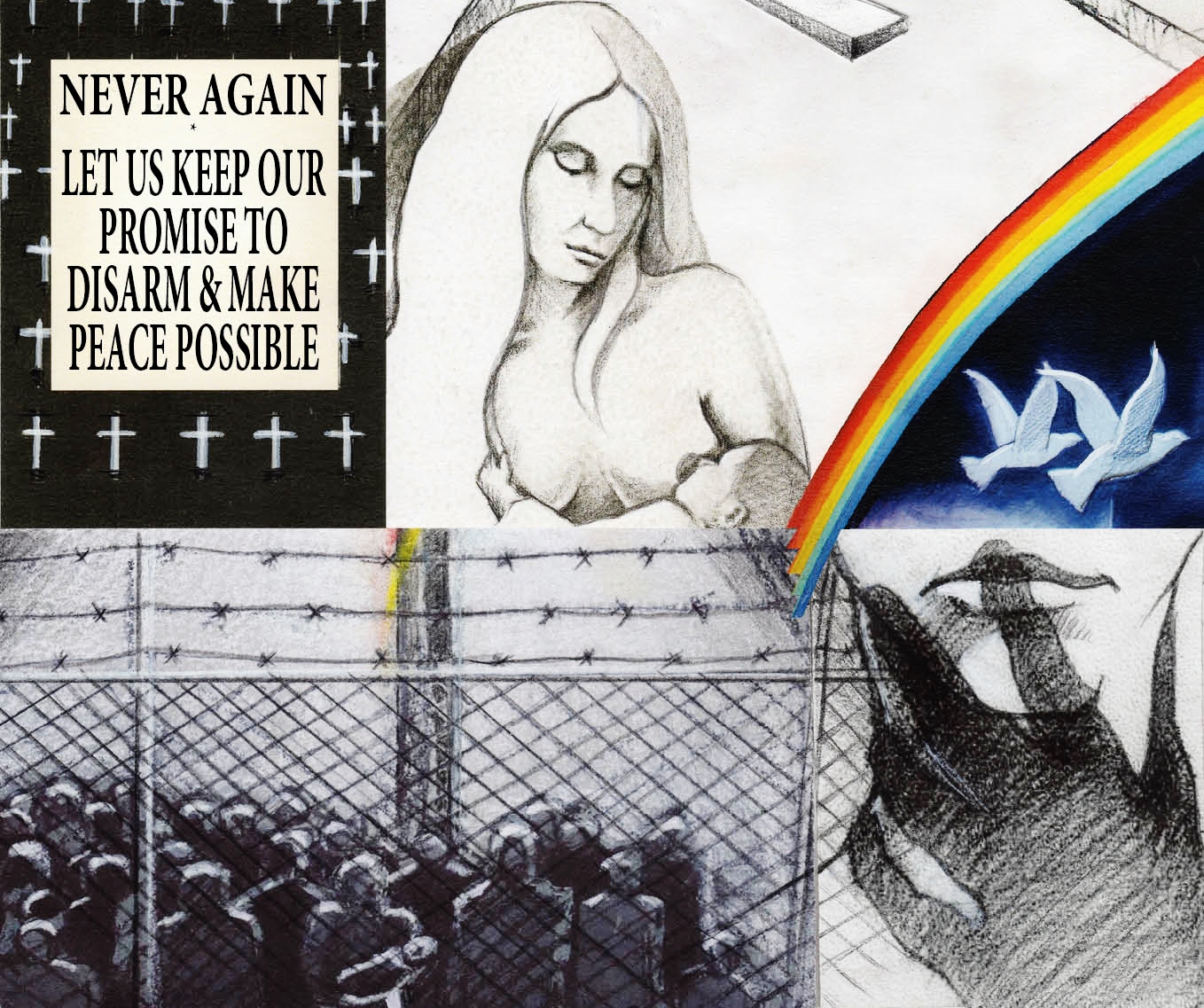

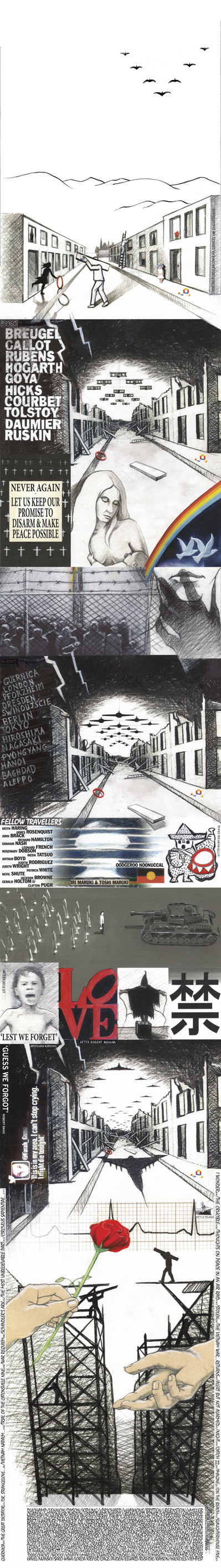

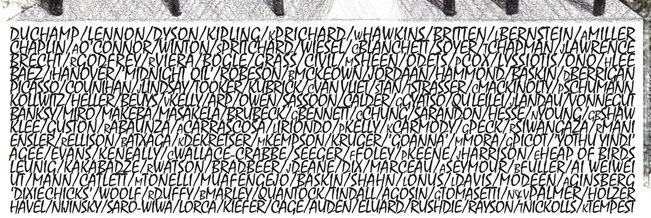

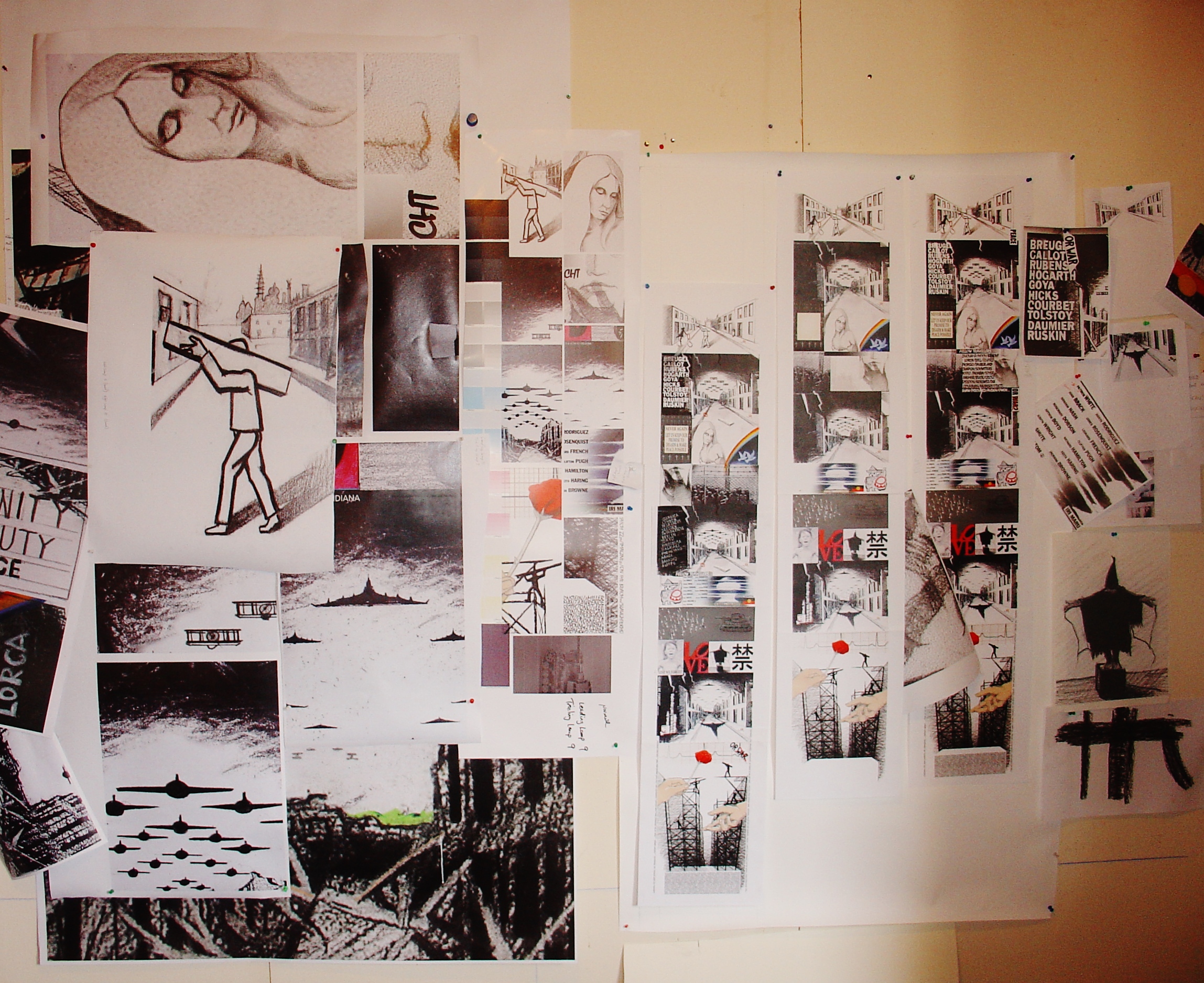

It is very sad that Australia, in some ways, rates below Turkey when it comes to protecting our national heritage and Australian federal and state governments lack the backbone to rise and make a stand for the national good. I feel that there is a moral obligation on all Australians to value our heritage and it also certainly makes a lot of economic sense as in the long term there is much more money in cultural tourism than in digging up dirt. We have already lost much. How much more will we need to lose before we will stand up to government and big business and say enough is enough? Give Peace a Chance Is the Peace Movement still relevant for our contemporary, post-truth, social media driven society? William Kelly is an artist who has devoted his life to giving peace a chance and working in socially engaged art. Born in Buffalo, New York, Bill Kelly remembers that he once called a park bench his home and found employment as a steel worker, taxi driver and welder. He was also awarded a Fulbright Scholarship and for a while served as the Dean of the Victorian College of the Arts. He now works from a studio in rural Victoria and makes art that has received widespread recognition. Kelly is soft-spoken and quick to describe himself as the luckiest artist alive, in a quiet, but consistent manner has devoted his life and art to the peace movement and is widely considered as the moral conscience of Australian art. He is a gifted, and at times brilliant, natural draughtsman, who frequently weaves his compositions together like a tapestry allowing the accumulated power of the images to develop a singular strong and dominant voice. Between August 2014 and December 2016 Bill Kelly has been a recipient of a Creative Fellowship at the State Library of Victoria with the initial idea of developing an artists book dealing with socially activist art in Australia, but the idea morphed in form, scale and theme. The intimacy of the artists book was swapped for the most public of art forms, the banner, and a private whisper became a public declaration. Banners have always been a public art and in many instances have been associated with peoples’ movements, whether this be May Day demonstrations or the Banners of Pride created by trade unions over the ages. The State Library of Victoria has its iconic domed reading room that I consider as one of the most beautiful spaces in the world and one in which I have spent many years of my life. Bill Kelly’s idea was to create a grand Peace Banner, in the form of a twelve-metre-long print, that would be suspended from the dome in the public reading room. Technically this is one of the largest fine art prints made in Australia, possibly only rivalled by the thirty-five-metre long screenprint made at Megalo in Canberra to commemorate its thirty-five year history . Bill Kelly’s work, titled Peace or War: The Big Picture, has as its basic compositional unit a street scene where elements from Giorgio de Chirico, Balthus and Georges Seurat – three of the artists who have changed the way we see the world – contributing iconic elements to the design. This composition is then repeated several times on the banner stressing how society by employing different technologies constantly sets out to destroy the same social fabric. The street remains the same as do the human victims, what changes are the technologies employed to kill people, from primitive means to American stealth bombers. At the bottom of the banner is a dense block of handwritten names of the ‘foundation’ consisting of the names of those who thought that social norms should be challenged and needed to be changed. Amongst the more than a hundred names are included Marcel Duchamp, Noel Counihan, Lin Onus and Salman Rushdie . The fundamental question posed in this banner is why should society regard war as a norm and peace as an interlude and not consider peace a basic human right. Bill Kelly poses the big question on a grand scale and he is one of the few artists who has the skills, imagination and the ability to pull this off to create something which possesses a solemn beauty, a monumental presence and punches a strong message. While a philosophy prevails among some artists that artists should not in their work make overt political statements and that this belongs more to the realm of politicians and social commentators, Kelly looks to the tradition of Goya, Picasso and Rivera and sees the role of the artist to engage with society and be both the visual chronicler of their time as well as the conscience of their society.

In a world that sometimes appears to be hurtling along a path of self-destruction and within a milieu of art making that has lost itself in pattern-making and self-centred esoteric theory, Bill Kelly’s art brings together two democratic art mediums, that of printmaking and the banner, to produce a powerful work that shouts its message to give peace a chance. This is a celebration of the values of the State Library of Victoria to be free, democratic and secular and a strong affirmation that art has the power to alter society and to join the ranks of those who are fighting the good fight. It is critical for us to remember that despite all obstacles, peace must win as the alternative is too frightening to even contemplate. William Kelly’s banner in the Dome Reading Room of the State Library of Victoria, Peace and War: The Big Picture, will remain on display until Sunday December 11, 2016 |

GRISHIN'S ART BLOG

Sasha Grishin AM, FAHA is the author of more than 25 books on art, including Australian Art: A History, and has served as the art critic for The Canberra Times for forty years. He is an Emeritus Professor at the Australian National University, Canberra; Guest Curator at the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne; and Honorary Principal Fellow, Faculty of Arts, at the University of Melbourne. Archives

June 2024

Categories

Keep up-to-date with Sasha Grishin's blog with the RSS feed.

RSS offers ease of access and ensures your privacy, as you do not need to subscribe with an email address. Click here to download a free feed reader |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed