The Schoolgirls of Charles Blackman Charles Blackman first came to prominence in the early 1950s when he exhibited his schoolgirl series of paintings and drawings in Melbourne. Although subsequently his Alice in Wonderland series gave him national acclaim, the schoolgirls remained an ongoing source of inspiration and, for the first time, a good cross-section of these paintings and drawings has been assembled at the Heide Museum of Modern Art. The paintings have aged, perhaps not particularly gracefully, and in their style, conception and execution appear very much of their time. While all art may be a witness of its epoch, Sidney Nolan’s Ned Kelly pictures of 1946-47 are to some extent ageless and today have a contemporary freshness and immediacy of the here and now. The Blackmans belong to the 1950s. The mixture of enamel with oils or tempera on cardboard or masonite is of its time, as is the middle ground on which figurative expressionism, surrealism and traditional representational art meet and combine in an uneasy association. The long-cast shadows, huge eyes, simplified palette and the sense of patterning have a multitude of parallels in preceding European painting, especially Odilon Redon and Marc Chagall, the work of the American Ben Shahn, as well as the Australians Danila Vassilieff, Bob Dickerson, Arthur Boyd, Sidney Nolan, Leonard French, Jon Molvig, Joy Hester and John Brack. The Sydney-born Blackman, by the time he was twenty, moved up to Brisbane where he met his future wife Barbara née Patterson with whom he moved and settled in Melbourne in 1951. Speaking of his schoolgirl series, in retrospect, to the poet Thomas Shapcott, Blackman observed “I just started drawing my schoolgirl pictures; they just came out. That was it. It takes a long time to get to the door; once you pass through the veil or once you pass through the surface of the idea then it all comes pouring out. The schoolgirl pictures had a lot to do with fear, I think. A lot to do with my isolation as a person and my quite paranoid fears of loneliness and stuff like that; and indeed you could almost say why I painted them.” Apart from this cathartic quality, while already working on the series, Blackman was introduced to the wonderful verse of John Shaw Neilson by Sunday Reed, that seemed to give him permission to project his own feelings for loneliness and alienation into his subject. In fact, he quoted Neilson’s Schoolgirls hastening, as the epigraph for his exhibition: Fear it has faded and the night. The bells all peal the hour of nine. Schoolgirls hastening through the light Touch the unknowable divine It has been well-documented that Blackman was aware at the time of the abduction and murder of children, as well as of the murder of a student friend of his wife, and a menacing and sinister note permeates many of the works. There is a quality of a haunting presence, where the schoolgirls seem trapped within a disturbing claustrophobic space – the encounter of innocence with a world in which danger and an oppressive feeling of unease lurk. However, for all of this sense of imminent menace, Blackman’s schoolgirls exist within an age of political innocence. Today, the idea of a male artist making a major series of paintings about schoolgirls, or about any sort of children, sits uncomfortably with the public. It may have been the unenlightened stupidity of politicians that gave oxygen to the shameful Bill Henson episode, but there was enough public suspicion and vitriol to permit the issue to run in the public arena. I remember once asking John Brack why there were so many images of schoolgirls in his art and that of his contemporaries in the 1950s and, instead of some profound existential answer, he simply sighed and pointed out to me that at the time he had four young daughters and many of his peers also had children and, coincidently, most of them had a predominance of daughters. Blackman may not have been portraying his own children; his first daughter Christabel was not born until 1959 and his first son Auguste in 1957, and may have projected his own fears and anxieties onto schoolgirls as a convenient visual metaphor, but public perception has swung so markedly that it leaves little room in serious art making for a Chagall or Blackman painting adolescent girls. Back in the 1950s Blackman was more under attack for his style and technique, than for his imagery. As I moved around the exhibition what I admired the most was Blackman’s ‘awkwardness’ in draughtsmanship, the images may have flowed out once the floodgates of the imagination opened, but the drawings have the quality of constant toughness.

About the paintings, the artist noted his “great struggle with the paint” and one can see evidence of constant experimentation, grittiness of the surfaces and a fecundity of invention. I think of them as some of the best paintings that he ever made, at a time before his style became mannered and the sugar content in the imagery increased. While it is possible in Blackman’s Schoolgirl series to detect a myriad of sources and influences, which one would anticipate in the work of an artist aged in his early twenties, they are some of the most memorable and original works to appear in Australian art in the early 1950s. Charles Blackman: Schoolgirls Heide Museum of Modern Art 4 March – 18 June 2017 This blog is being published in conjunction with The Conversation https://theconversation.com/profiles/sasha-grishin-143423

1 Comment

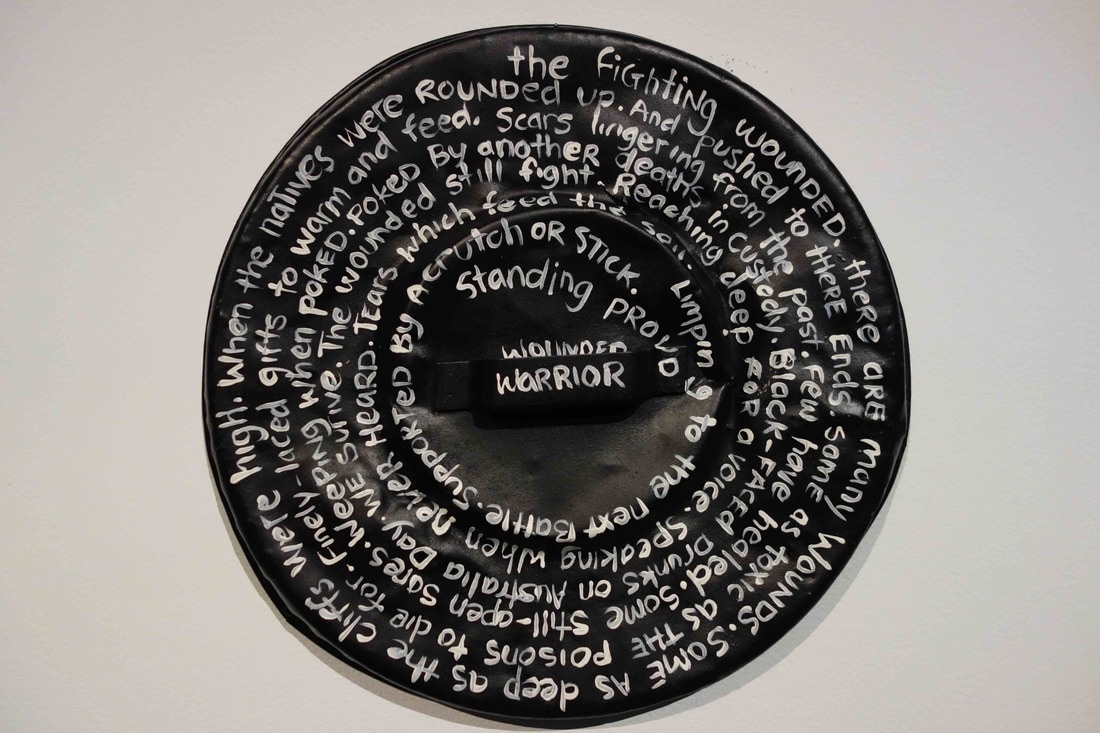

Institutions exhibiting contemporary Australian art When the National Gallery of Victoria presented its Melbourne Now exhibition, late in 2013, it was greeted with a mixed critical reaction. Personally, I was very supportive as I love going to a high calibre exhibition in a major art institution where more than half of the 450+ participants are unfamiliar to me. It was dazzling and with a huge ‘wow’ factor even if, in retrospect, it may have appeared somewhat rushed with many major artists excluded and some of the more marginal ones given too much emphasis. What was exciting was the broad-brush approach and the preparedness for a leading Australian art institution to put on its walls and gallery spaces new, emerging and established local artists and designers. Later in 2017 the Melbourne gallery will present its inaugural NGV Triennial which will bring together 78 artists from 32 countries, but with only nine artists from Australia. The Adelaide Biennial kicked off in 1990 and, apart from the Art Gallery of South Australia, by 2016 it had spread to the Anne & Gordon Samstag Museum of Art at UniSA, JamFactory, Carrick Hill and the Santos Museum of Economic Botany in the Adelaide Botanic Gardens. More tightly curated than Melbourne Now and national rather than regional in its orientation, the focus has been on the more established names, rather than the emerging and potentially surprising revelations. Highlights in 2016 included Abdul-Rahman Abdullah, Pepai Jangala Carroll, Louise Haselton, Loongkoonan, Danie Mellor, Nell, Ramesh Mario-Nithiyendran, Gareth Sansom, Robyn Stacey, Garry Stewart and the Australian Dance Theatre, Tiger Yaltangki and Michael Zavros. The appointment of Erica Green (Director of the Anne & Gordon Samstag Museum of Art) as curator of the 2018 Adelaide Biennial means it will be in a safe pair of hands with another strong crowd-pleasing selection. Australian art has always been the Achilles’ heel of the Sydney Biennale since its inauguration in 1973. Its primary function was to bring Australian artists and art audiences up to date with the latest developments in international art (such a 1950s notion!) and include Australian artists that would usually make the international selection look good. Despite the generosity of its main sponsors, the Sydney Biennale has always been poorly funded and appeared as the poor cousin of the big biennials and triennials abroad and decisively shabby compared with big art fairs such as the Frieze circuit and the Art Basel circuit. The Australian Perspecta commenced as a biannual exhibition in 1981, held in alternate years to the Biennale, and designed as a showcase for contemporary Australian art practice. When the Australian Perspecta moved out of its home at the Art Gallery of New South Wales to take on other venues in Sydney, following in the footsteps of the Biennale, it seemed to lose focus and definition and quietly folded in 1999. Since then Sydney has had no regular exhibition dealing exclusively with contemporary art practice, at least until now. The National: New Australian Art opened across Sydney in April 2017 at three venues – the Art Gallery of New South Wales, the Museum of Contemporary Art and the Carriageworks. The name is silly, as I pointed out in my review for the Fairfax media, a cross between a political party and the antiquated idea of a national school of art, but it is accompanied with a sensible catalogue and an excellent website. It is a collaborative exhibition, which is equally funded by the three venues, with funding committed for six years, in other words for two more biennials. It is national, with artists selected from every state and territory, and the selection was made by five curators from these institutions, namely, Anneke Jaspers and Wayne Tunicliffe from the Art Gallery, Lisa Havilah and Nina Mial from the Carriageworks and Blair French from the Museum of Contemporary Art. Apparently, these curators established a checklist of about 200 names, which was whittled down to the 48 artists included in the exhibition. For the next biannual there will be a new set of curators. Unlike Adelaide, there are no ‘golden oldies’ in the mix but, unlike Melbourne Now, there are no real surprises. They are all artists known around the traps with an average age in the forties. The geographic spread also dilutes any real focus and, to betray a personal prejudice, I feel that the state galleries should in shows of this nature first and foremost represent artists from their region and leave the national picture to the national institutions in Canberra. This said, there is much in the selection of artists to recommend the exhibition. Going by institution, at the Art Gallery in the foyer are powerful and confronting large-scale paintings by the late Gordon Bennett interrogating the use of Aboriginal patterns in decorative arts for white people proposed by Margaret Preston. Emily Floyd’s Kesh alphabet, for all of its imposing polychrome monumentality, is really quite a funny piece about a female orgasm as expressed in the fictitious feminist language of Kesh. Downstairs is Yhonnie Scarce’s amazing installation Death Zephyr, where a vast array of hand-blown glass elongated long yams, bush bananas and bush plums, relating to this artist’s Kokatha and Nukunu heritage with her land adjoining the prohibited zone of the test site at Maralinga. The whole thing hovers like a menacing dark, toxic cloud. Megan Cope, a Quandamooka Nation artist, in her Re Formation part 3, (Dubbagullee) builds a large mound of cement-cast oyster shells layered with black sand and copper slag. Indigenous shell monuments made of oyster shells were destroyed by colonial settlers and were frequently burnt for lime to make cement. It is one of those pieces where the attractive bewildering intricacy of detail conceals a dark force, a sense of longing for that which is now lost. One could observe that each venue carries the traces of its own DNA, the sense of tradition and collection at the Art Gallery, for example Bennett references Preston in his paintings; at the Museum of Contemporary Art, the sense of design, installation and the conceptual, for example Gary Carsley, Marco Fusinato and Peter Maloney; while at the Carriageworks, the idea of performance, industrial scale and Indigenous heritage, such as the flags and banners of Archie Moore and the brilliant performances by the veteran Kimberley artist, Alan Griffiths. At the Carriageworks, I was captivated by the work of the Wiradjuri artist Karla Dickens. I was familiar with her fabric work, but the Fight Club series is striking and unexpected. The series consists of eight metal rubbish bin lids, painted black, on which are inscribed in white lettering powerful blank verse as a continuous clockwise script. The lids appear like modern urban shields highlighting the culture of violence in Australian society.

The Museum of Contemporary Art has a number of memorable pieces including Julia Gough’s The gathering, a powerful and evocative video installation about loss in her native Tasmania and Matthew Bradley’s wacky homespun installation, like a handmade junk heap. Ronnie van Hout, a New Zealander based in Melbourne, creates a complex room-size installation on the principle of “when in doubt, put it in”. Highly self-referential in many of its aspects, the piece negotiates a space where gothic horror meets the uncanny and the surreal. It is powerful, disturbing, eerie and quite unsettling, even in small doses. For me, the brickbat award goes to Khadim Ali’s Arrival of demons mural in the entrance staircase of the museum. The only redeeming feature is the knowledge that it will be replaced in twelve months and, in the meantime, it will attract countless selfies for those who are drawn to pretty glam horror. Khadim Ali’s piece is an acquisitive site-specific installation, however many of the other exhibits are non-acquisitive commissions made for this exhibition. The National is a serious attempt made to revive the Australian Perspecta model and highlights the critical need for dedicated exhibitions of contemporary Australian art practice, which lack the constraints of commercial art galleries and art fairs and the hidden irrelevance of many of the small art spaces. Although it is largely dedicated to ‘biennale-style art’ it is a step in the direction of making local Australian visual culture accessible to the local population. The fact that major art institutions can collaborate on a single show must be a good thing for the future health of Australian art. |

GRISHIN'S ART BLOG

Sasha Grishin AM, FAHA is the author of more than 25 books on art, including Australian Art: A History, and has served as the art critic for The Canberra Times for forty years. He is an Emeritus Professor at the Australian National University, Canberra; Guest Curator at the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne; and Honorary Principal Fellow, Faculty of Arts, at the University of Melbourne. Archives

June 2024

Categories

Keep up-to-date with Sasha Grishin's blog with the RSS feed.

RSS offers ease of access and ensures your privacy, as you do not need to subscribe with an email address. Click here to download a free feed reader |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed