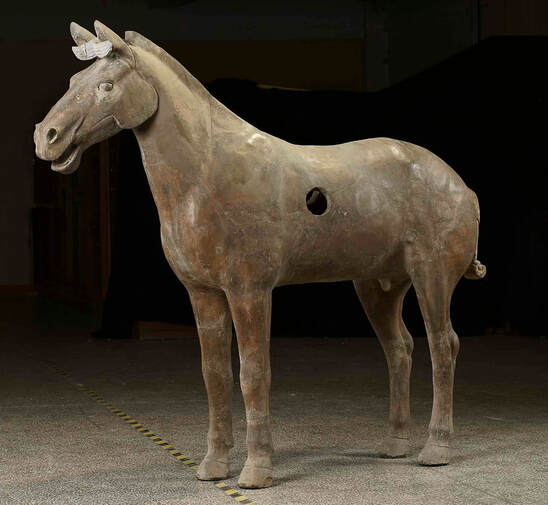

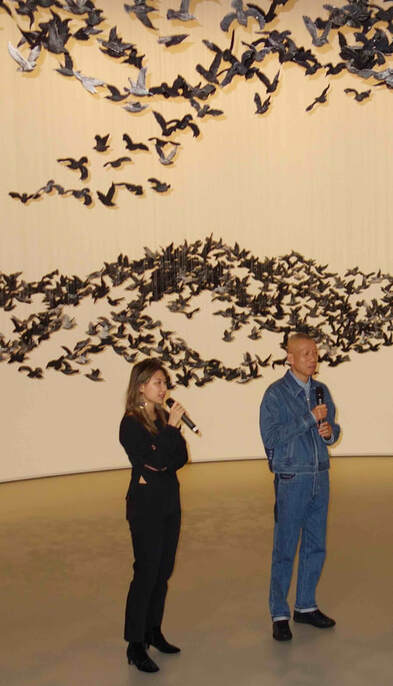

Terracotta Warriors & Cai Guo-Qiang: A contemporary perspective on ancient history Since they were first uncovered in 1974, the thousands of Terracotta Warriors guarding the afterlife of Qin Shi Huang (259-210BC), the first Qin Emperor of China, have been on the move advancing the political, cultural and artistic policies of the Peoples’ Republic of China. The mausoleum of Qin Shi Huang in Lintong County, outside Xi’an in Shaanxi province, China, about thirty-five metres underground, is a very popular tourist site and presently attracts about 30,000 visitors a day. In all, it is estimated that there are about 8,000 warriors, 130 chariots, 520 horses, 150 cavalry horses and other pits containing non-military figures, including court officials, acrobats, performers, bureaucrats and musicians. Only a fraction of this huge figurine group has been fully excavated. Despite the romantic theory that each figure is unique and individualised, there were a number of casts – for example, ten basic face types – and many of these were manipulated slightly while the clay was still wet. The figures were assembled from a limited number of stock parts to create the impression of a huge differentiated army. The figures are hieratic – a general tallest at 196cm, others a bit smaller – and vary in uniform and hairstyle in accordance with rank. There was also a variety of poses. Originally the figures were polychrome – pink, red, green, blue, black, brown, white and lilac – and they held real weapons. On exposure to air, the colours quickly faded and the weapons powdered away leaving only fragments. Excavations are paused until conservation techniques can be refined to preserve the original appearance of the work. Emperor Qin Shi Huang was a cruel despot obsessed with power, the burning of books and megalomania, with an estimated 700,000 workers labouring on his tomb. Nevertheless, he introduced many legal, monetary and language reforms and commenced the building of the Great Wall. On his death many of the labourers, concubines and the emperor’s inner circle were incarcerated and perished in the tyrant’s tomb to seal the secret of its location. His dynasty was short-lived and his successors of the Han Dynasty turned their backs on many of his excesses, but retained a number of the key reforms. The first time these archaeological artefacts toured overseas was in 1982 and it was to the National Gallery of Victoria and then onto the Art Gallery of New South Wales. Subsequently they have marched all around the world, in many places attracting record crowds only to be rivalled by the archaeological exhibit of King Tutankhamun from Ancient Egypt. They were also shown again in Australia at the Art Gallery of New South Wales in 2011. The Chinese state carefully controls the exposure of the terracotta warriors abroad, with each venue allowed only ten figures – the British Museum in 2007 was the exception with twelve figures. The National Gallery of Victoria has selected eight warriors in a variety of poses, plus two beautifully articulated horses. The genius of the Melbourne display lies not in terracotta warriors, shown in their mirror cases, nor even the 160 archaeological objects drawn from museums across the Shaanxi province (that in many instances are more interesting than the restored terracotta figures), but the juxtapositioning of the ancient art with the contemporary vision of Cai Guo-Qiang. Cai, born 1957 and since 1995 largely based in New York, in many ways presents a lyrical, contemplative and humanist alternative to the brutalist art of Emperor Qin Shi Huang. The emperor sought to dominate the environment through a show of power and force: Cai reapproaches the environment surrounding the tomb – the soil, the flowers, trees and the fauna – that ultimately seem to dominate even the emperor’s wish for immortality. The leitmotif throughout Cai’s commentary on the ancient art is the starling – a bird found in the region of the tomb. Cai has created a great swarm of ten thousand suspended blackened porcelain starlings that appear from a distance almost like a traditional Chinese ink landscape painting. It is something like the souls of the perished entombed under the ground. Cai observes, “The ever-changing formation of 10,000 porcelain birds seems to embody the lingering spirits of the underground army, or perhaps the haunting shadow of China’s imperial past. But in this age of globalisation, aren’t they also forming a mirage, an exoticised imagination of the cultural other?” Peonies and cypress trees, which grow in the area, are celebrated in porcelain constructions as well as in vast gunpowder drawings. Whereas the imperial art was ridged and disciplined, gunpowder drawings on silk and paper invariably involve the element of chance and unpredictability. Forms emerge darkly, recognisable, but as if seen from a great distance. Through the use of materials associated with China – porcelain, silk, paper and gunpowder – Cai reverts to tradition to make an unexpected commentary on antiquity that is ever-present and reasserting its power. This is a complex, powerful and absorbing exhibition, where through the unexpected intervention of a contemporary artist, ancient forms are given a new life and a new meaning. Melbourne Winter Masterpieces: Terracotta Warriors & Cai Guo-Qiang, National Gallery of Victoria, International, 24 May-13 October 2019

1 Comment

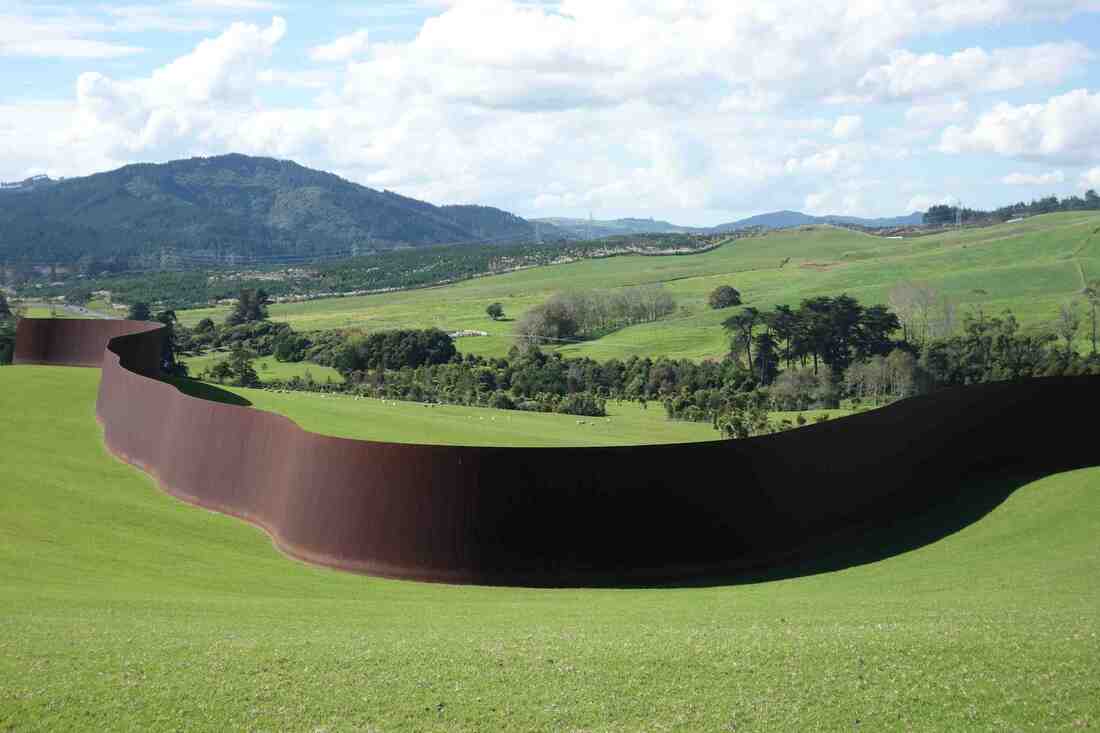

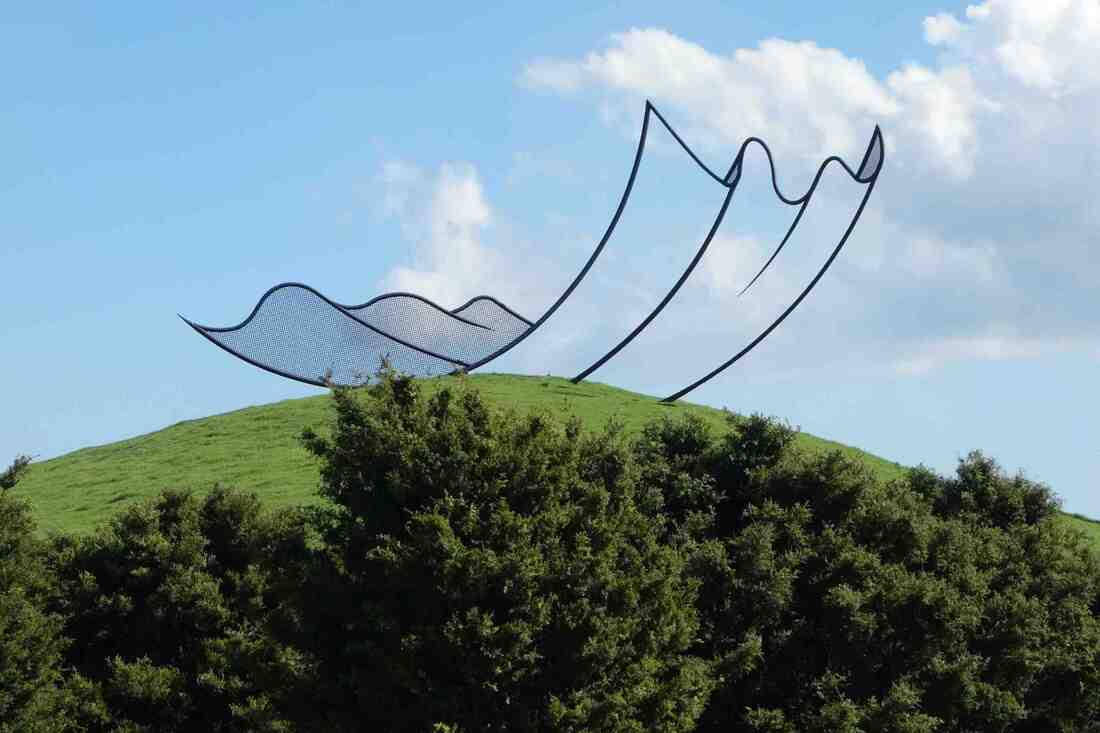

Gibbs Farm – the destination sculpture park Is Gibbs Farm the most picturesque and the most significant sculpture park in Australasia? Gibbs farm, about an hour’s drive north of Auckland, New Zealand, is a 400 hectare property whose western boundary is flanked by the spectacular Kaipara Harbour – the largest harbour in the Southern hemisphere. The property was acquired by the businessman Alan Gibbs in 1991 and populated with roaming herds of zebras, Tibetan yaks, bison, giraffes, ostriches as well as sheep, alpacas, deer, swans, emus and peacocks amongst other animals. What makes the farm unusual is the 27 monumental sculptures that are dotted around the property, some by the world’s most renowned sculptors and, in a number of instances, the largest and most ambitious works by these artists. Gibbs Farm has developed something of a legendary reputation – more spoken of than experienced at first hand. The farm is private and, although entry is free, it is devilishly difficult to gain admission. I have met people who have waited three years for their chance to see this open-air sculpture park; others have conspired for years from overseas or joined rather expensive fund-raising art tours. I have been fortunate to visit Gibbs Farm twice, in 2017 and May 2019, both times in perfect weather. Alan and Jenny Gibbs have been art collectors for decades and on Gibbs Farm the idea was to challenge the artist with a site-specific installation with few financial or logistical constraints. One of the great highlights is Richard Serra’s Te Tuhirangi Contour, 1999/2001. Running a breath-taking 257 metres, it is an elegant ribbon of steel winding across the landscape. It consists of 56 Corten steel plates, each six metres high and each weighing about eleven tons. The wall leans out eleven degrees from the vertical and seems to whimsically skim across the surface or, in Serra’s words, it “collects the volume of the land”. It is one of the most impressive monumental minimalist pieces that I have ever encountered and when you glance at the work more closely, about half-a-metre above the ground line there is a continuous subversive white mark. The cause is sheep rubbing against the warm rusty steel and in an unexpected way grounding the piece into the rural farming environment. Another memorable piece is Anish Kapoor’s huge Dismemberment, Site 1, 2009. Coloured bright red, it consists of an 85-metre long mild steel tube with tension fabric. To give it a context in scale, it is like an eight-storey high sculpture stretching a city block and has been located in a cut cleft within a high ridge. The scale is such that it is impossible to the see the whole work at a single glance from any angle (except perhaps from the air) and as you move around the work you are provided with additional elements to piece together this dismembered composition. The scale and glimpses of the landscape and the harbour add to the incredible ambience of the piece. One of the most perplexing and rewarding sculptures at Gibbs Farm is Sol LeWitt’s Pyramid (Keystone NZ), 1997, built up of standard concrete blocks with a base of sixteen by sixteen metres and a height of 7.75 metres. This founding artist of minimalism and conceptual art has created here a most remarkably sensuous sculpture. Although clearly made up of many modules of considerable complexity, the whole adds up to a beautifully simple single pyramid. The more you are absorbed by the intricacies of the piece the more striking and bold is the overall conception. The architectonic monumental character contrasts with the dissolving reflecting surfaces within the lush green setting. One of the beauties of Gibbs Farm is that one wanders through it as within an enchanted landscape. There is Daniel Buren’s meandering Green and White Fence (1999-2001), which I understand is still growing and now stretches to 3.2 km. Neil Dawson’s Horizons, 1994, sits on one of the highest hills in the sculpture park and through a tromp l’oeil strategy is suggestive of many different forms rich with associations. Andy Goldsworthy’s Arches (2005) consists of eleven seven-metre-long pink arches stretching into the sea made from Lead Hill sandstone blocks quarried in Scotland. It is a wondrous and mysterious creation that has now weathered and, between my visits, has increasingly taken on the appearance of the surrounding environment, seeming to have become one with the seascape setting. Gerry Judah’s Jacob’s Ladder (2017) is one of the more recent additions to Gibbs Farm, twisting and climbing 34 metres into the sky, and is made of 480 lengths of steel weighing 46 tonnes with a width of eight metres. From a distance, there is a lightness and airiness that disguises its mass and suggests a metaphorical ladder of revelation. |

GRISHIN'S ART BLOG

Sasha Grishin AM, FAHA is the author of more than 25 books on art, including Australian Art: A History, and has served as the art critic for The Canberra Times for forty years. He is an Emeritus Professor at the Australian National University, Canberra; Guest Curator at the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne; and Honorary Principal Fellow, Faculty of Arts, at the University of Melbourne. Archives

June 2024

Categories

Keep up-to-date with Sasha Grishin's blog with the RSS feed.

RSS offers ease of access and ensures your privacy, as you do not need to subscribe with an email address. Click here to download a free feed reader |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed