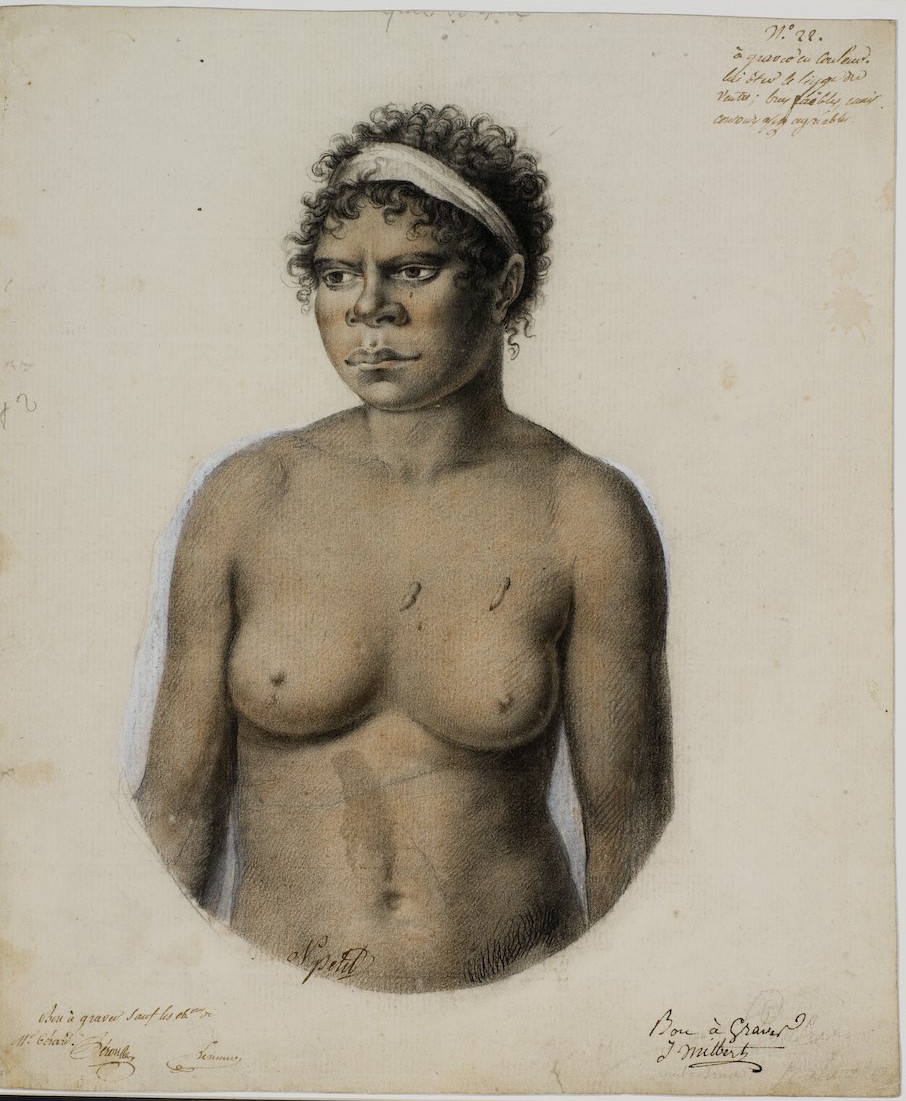

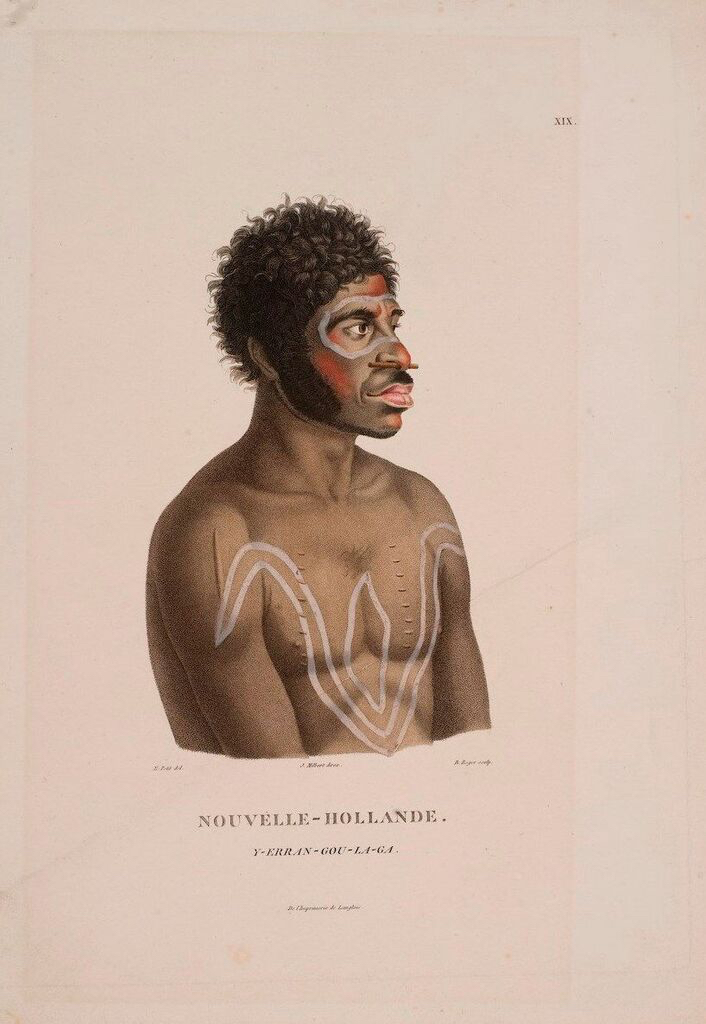

The French Connection in Australian art Long before Brexit the British and the French were rivals both in Europe and beyond. As colonial powers, Britain and France flexed their considerable naval muscle in establishing new colonies and trade routes, frequently within the spirit of hostile competition. The rise of Napoleon Bonaparte was generally viewed by the British with derision, as “the little corporal who built an Empire”, a type of Donald Trump of his time, who set out to disrupt British trade routes and colonial prosperity. The battle for colonial domination was fought out as far away as Australia and while the story of Captain Cook and the First Fleet is known to every school child, the French adventure is almost completely ignored. An exhibition devoted to the voyages of Nicolas Thomas Baudin to Australia from 1800 to 1804 has opened at the South Australian Maritime Museum in Port Adelaide before embarking on a two year national tour that will take the exhibition to Tasmania, Sydney, Canberra and Perth. As with Cook’s journey some three decades earlier, Baudin’s epic voyage answered to a number of different agendas in his home country, including political, economic and cultural. Citizen Baudin, as a patriotic Frenchman eager to serve the Republic, had already proposed to the French navy schemes to disrupt British trade and had earlier been frustrated by British authorities in Trinidad who had prevented him from reclaiming his possessions. In April 1800, the First Consul, Napoleon Bonaparte, personally signed a decree to fund and send Baudin as commander in charge of an expedition to explore New Holland and Van Diemen’s Land. Baudin, the Commander-in-Chief of the corvettes Géographe and Naturaliste, and his artists Charles-Alexandre Lesueur and Nicolas-Martin Petit, made their way to Australia. Lesueur and Petit, could be described as ‘accidental artists’, who were nominally appointed as ‘assistant gunners’ for the expedition, but once the three official artists absconded to the Île de France (Mauritius) in April 1801, six months into this epic journey that was to last three and a half years, they became the official pictorial chroniclers for the expedition. The survivors of the expedition returned to France in March 1804 and, three years later, the naturalist François Péron and Lesueur steered to fruition the publication of the first volume of the atlas Voyage de découvertes aux terres australes with forty-one lavish plates. Whereas British authorities frequently tightly control loans to the colonies, for example, scarcely more than half of the original History of the world in 100 objects exhibition left the British Museum to come to Australia in its original form, the French authorities said “oui” to pretty well everything. There are about 340 precious paintings and drawings from the Museum of Natural History in Le Havre, where most of the Baudin Australian material is housed; unique objects including Baudin’s chronometer; the original hand drawn maps and a most unexpected treasure, Baudin’s personal illustrated journal from the National Archives of France. Together with the other colonial powers, the French artists subscribed to the theory that by classifying and naming that which they encountered in the new world that lay beyond the pillars of Hercules, they would own it. The images of flora and fauna are initially sketched and observed with greatest fidelity to actual appearances, then they are classified to the most exacting categories of the Linnaean system and subsequently some are selected to be engraved, where they are subjected to the prevailing tastes in animal and botanical art of the period. While making my way around the exhibition, it became a sobering experience to see, time and time again, species that existed in Australia for thousands of years that were recorded by Europeans for the first time 200 years ago, now declared extinct because of the impact of these same Europeans. When it came to the depiction of Indigenous Australians, in contrast with the English colonists, Baudin’s artists seemed conscious of the values of “liberté et égalité” and left some of most empathetic images in first contact art. There was no perceived need to conqueror or ridicule, but simply to record and to testify to their existence. Attempts were made to write musical notation to local chants and possibly Indigenous people were invited to make their own drawings on the materials provided by the French travellers. All of these precious documents are included in the exhibition. Baudin never returned to France, but died on the return journey on 16 September 1803 on the Île de France and much of his heritage has remained neglected until recent times. Nevertheless, one may pause to ponder, what would have happened if the French had settled in Australia instead of the British or if they had established a colony in Australia as had been speculated in France and suspected by the British. English authorities constantly pre-empted the French, planting the Union Jack at every opportunity to announce that the land was no longer vacant and that the welcome mat had been removed. Exhibition Itinerary

South Australian Maritime Museum: 30 June – 11 December 2016 Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery: 7 January – 20 March 2017 Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery: 7 April– 9 July 2017 Australian National Maritime Museum: 31 August – 26 November 2017 National Museum of Australia, Canberra: 15 March – 11 June 2018 Western Australian Museum: September-December 2018

4 Comments

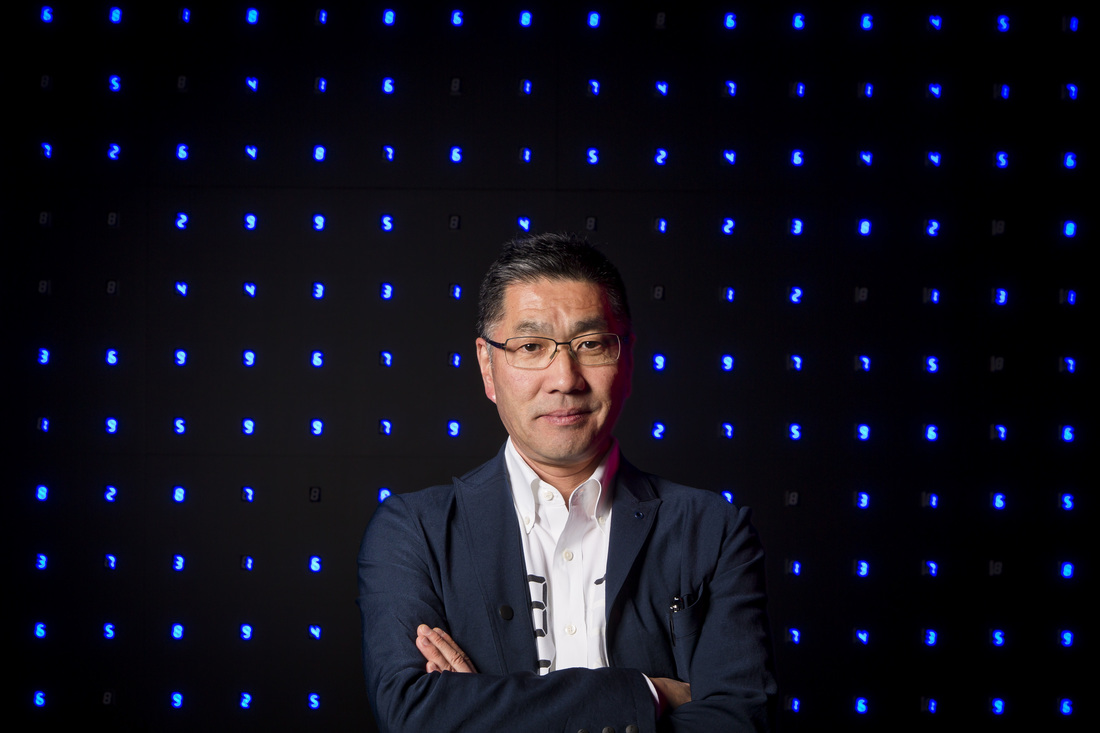

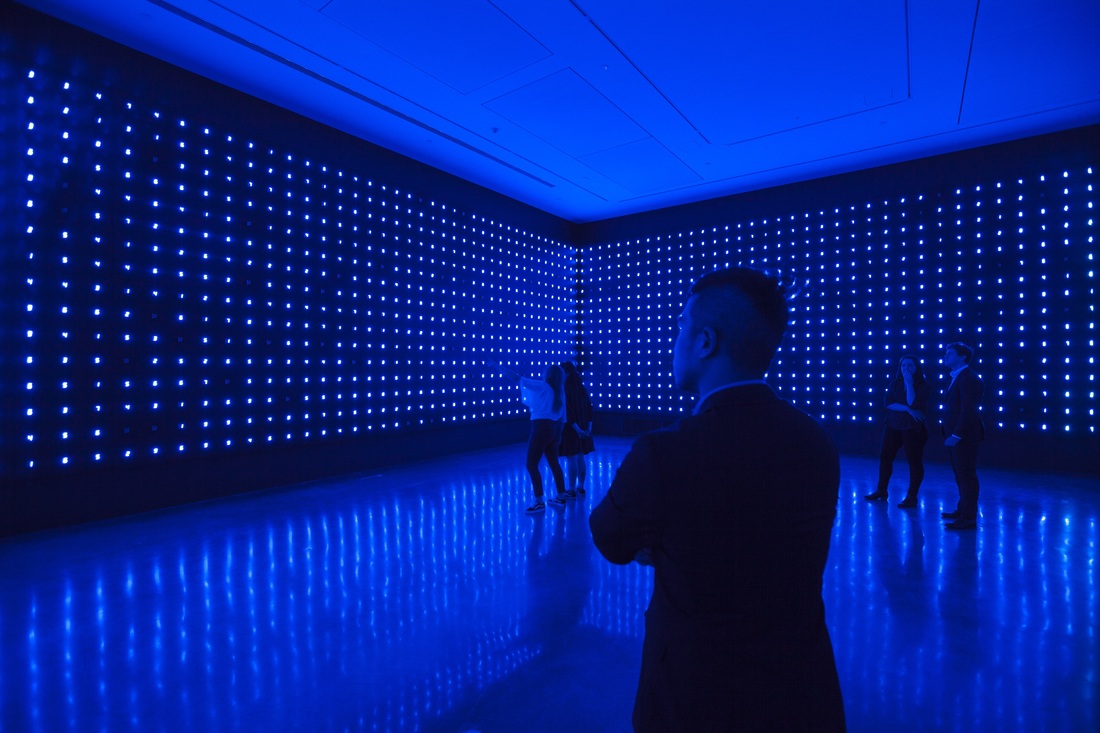

The Summer Blockbuster Summer is in the air and an end of the year blockbuster exhibition is coming to a gallery near you. In case you have missed it – this year’s theme is ‘immersive’ – all of the shows have to be immersive. At Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art there is a survey exhibition of the Japanese artist Tatsuo Miyajima: Connect with everything built around several immersive installations. The central motif in Tatsuo Miyajima’s art is the digital counter, something that counts down numbers from 9 to 1 on a small LED screen, originally in red or green, but now also available in blue and white. He identifies this with a peculiarly Buddhist way of thinking where at the end of 1, the system ‘reboots’ and starts again on a new cycle as you are reincarnated into a new manifestation. This is in contrast to the Western mode of thought, where after 1 comes zero and you simply die. He refers to them as his ‘performing objects’, where each one can be thought of as standing for a single life, so that a multiplicity of digital counters stands for a whole society. One of his immersive installations is called Mega Death, 1999, which consists of quite a large room with thousands of these little LED digital counters each counting down from 9 to 1 and then momentarily blacking out and then resurrected in their new existence. The counters are all blue – a symbolic colour for life. At a particular moment in time, they all black out and you are standing in a completely darkened room and slowly, one by one they flicker back to life and the whole of society is resurrected. Mega Death was initially commissioned for the Venice Biennale and the artist saw it as a challenge to summarise the 20th century and wanted to stress that the peculiarity of the century in his mind was human annihilation on an industrial scale, especially after the American bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It is simple, but effective, with whole exhibition interpreted as a meditation on the shape of time. Melbourne’s great immersive exhibition is David Hockney: Current that surveys what the artist has been up to over the past decade. During this time he had moved back to his native Yorkshire, and gone all digital with iPhones and iPad pressed into the service of art making. After a grisly accidental death of one of his young studio assistants, Hockney and his entourage moved back to California, where at the age of 79 he shows no signs of slowing down. It is a deliberately overwhelming and disorientating exhibition, where the artist moves from traditional oil painting and painting with acrylics, to drawings on iPads, moving images and immersive installations. Gallery publicity speaks of 1200 works in the show and with the mesmerising and constantly changing images, this could prove to be a conservative estimate. The Bigger trees near Warter (2007), ironically subtitled “ou peinture sur le motif pour le nouvel age post-photographique” (or en plein air for the new post-photographic age), measuring a massive 459 x 1225 cm, consists of 50 rectangular canvas panels and focuses on a huge tree within a wooded setting, where each panel is painted outside and from the object. The composition had been photographically spliced together so that all of these painted panels appear to seamlessly combine into a single picture. This is possibly the largest out of doors painting ever attempted. In the installation in Melbourne, photographic reproductions of the painted panel are created on the neighbouring walls to evoke an immersive experience. Personally, I found the painting itself through scale and colour pitch so intense, that the copies on the surrounding walls appeared as a bit of a distraction. A more successful immersive experience is his The four seasons, Woldgate Woods (2010/11) where on four large screens, we have a glimpse of the same section of the Yorkshire landscape captured in summer, autumn, winter and spring. Using a technology not dissimilar to Google streetscapes, Hockney photographed each season employing 9 cameras mounted on a vehicle and shooting simultaneously. The result is a four-and-a-half minute loop on 9 split screens that are combined into a single image on a single screen. When sitting on the couch in the middle of the room and surrounded by the four screens with the four seasons, it becomes a meditative experience that effectively plays with our perception of time and the geographical space. The Hockney exhibition is that of an artist in a hurry convinced in his own genius and happy to leave his oeuvre unedited. Many of the paintings are awkward, some of the digital drawings are slight and the neon pinks and hot greens are a bit painful on the retina. Nevertheless the pulsating energy, the love of risk taking and sense of defiance give this exhibition life and present the artist as a cigarette puffing maverick who refuses to age gracefully and, with vigour and aggression, constantly seeks to reinvent himself. At the Art Gallery of New South Wales you can immerse yourself into a sea of nudes, most of which are drawn from the collection of the Tate. It is a very uneven selection with a few dazzling highlights, including Pierre Bonnard’s The bath, 1925 and a selection of work by the wonderful Louise Bourgeois. Unlike their summer exhibition last year with a silly title, The greats: Masterpieces from the National Galleries of Scotland, which was a compact and terrific show and a runaway success for the gallery, the Nude is a spot drab and a spot uninteresting. Finally, the National Gallery of Australia promises a fully immersive exhibition of the treasures of Versailles with personal items from Louis XIV to Marie Antoinette. Perhaps the present incumbents at the Lodge will identify with the show and give the gallery some cake to eat, as presently it is starving, together with many other Australian art institutions. Perhaps one day the Australian public galleries will get over the idea that we need blockbusters every summer and the Australian art public will stop demanding them. To the best of my knowledge, none of these immersive exhibitions will be travelling to other venues in Australia. Tatsuo Miyajima: Connect with everything, Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, November 3 – March 5, 2017

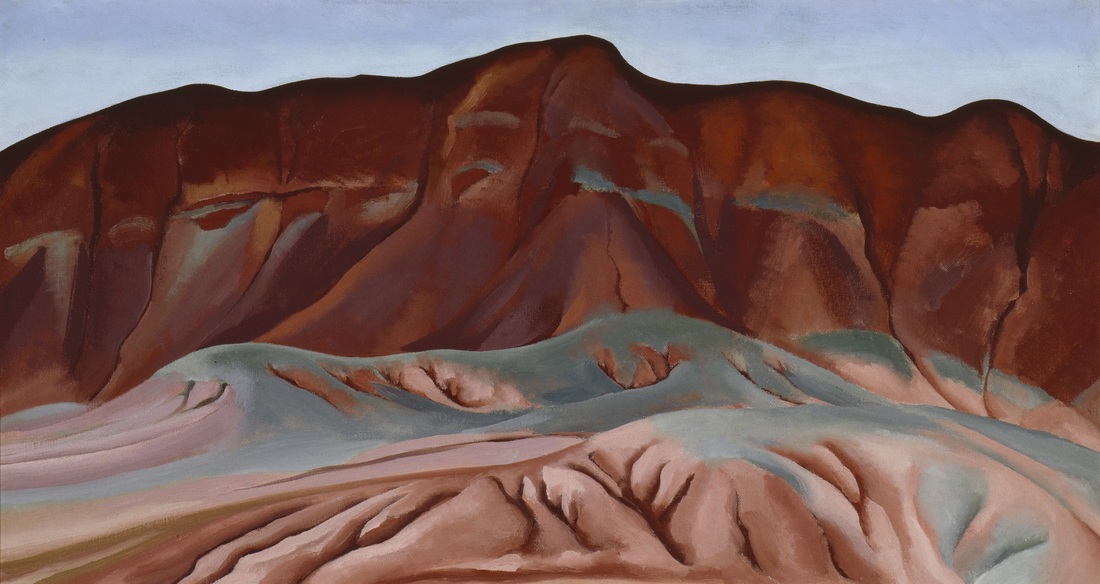

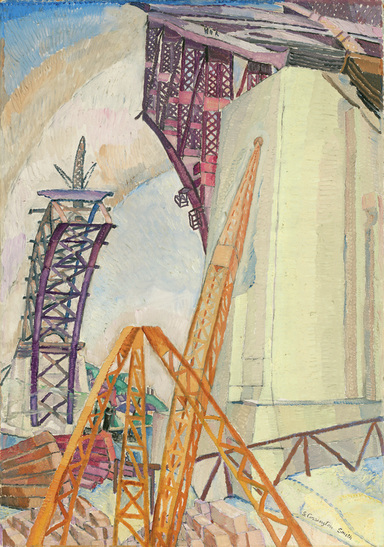

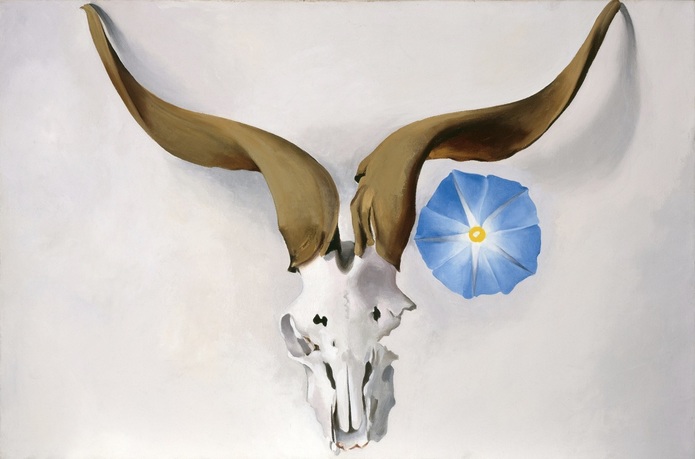

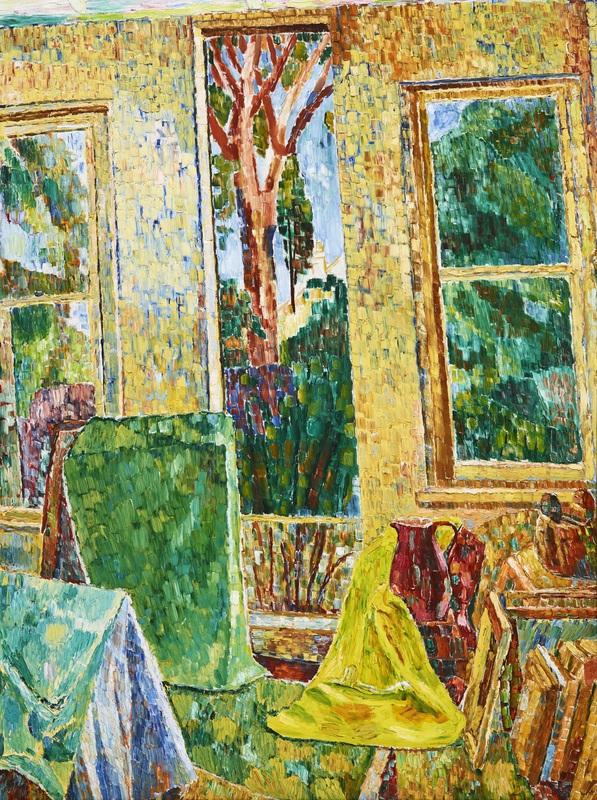

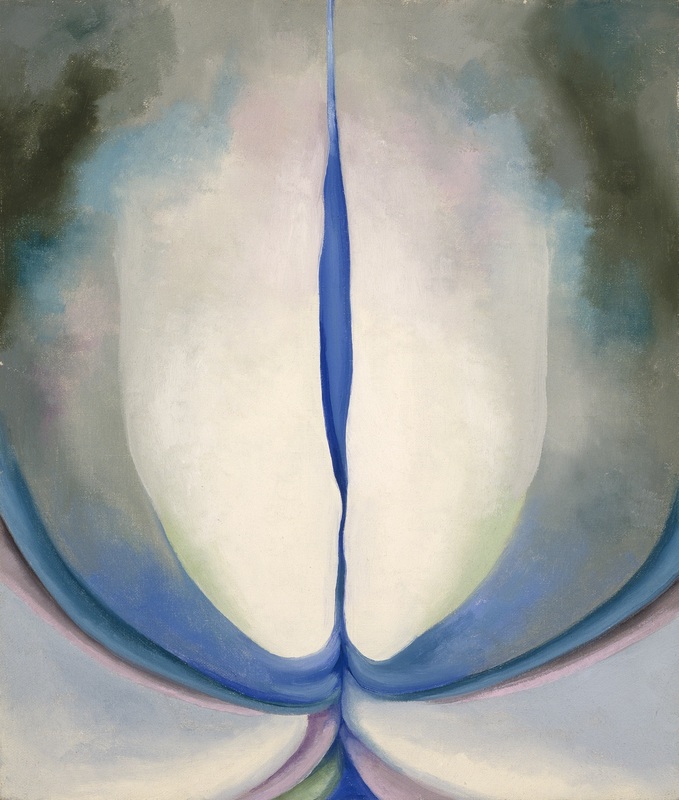

David Hockney: Current, National Gallery of Victoria, International, St Kilda Road, Melbourne, November 11 – March 13, 2017 Nude: Art from the Tate collection, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, November 5 – February 5, 2017 Versailles: Treasures from the Palace, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, December 9 – April 17, 2017 The women artists who created modern art Georgia O’Keeffe, Margaret Preston and Grace Cossington Smith in their parallel existences shared much in common. They were all born in the closing decades of the 19th century, they were blessed with longevity, averaging 92 years, and they were viewed as trailblazing modernists in their respective countries. In each case the overwhelming majority of their oeuvre remains in their home countries – O’Keeffe in American collections, while Preston and Cossington Smith in Australia. Consequently, these three women modernists are well known in their respective countries and figure in their national constructs of modernism, but less so abroad. O’Keeffe, this year is being fêted with a major show at the Tate in London, exactly a century after her debut in New York, Preston and Cossington Smith remain Australian national secrets. The show at Heide that unites these three artists was instigated by its former director Jason Smith and subsequently travels to Brisbane and Sydney. It brings together about thirty works from each artist, but one has to admit that the selection of work is uneven. The O’Keeffe selection is exclusively from the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe, New Mexico and, while it is representative of her oeuvre with skulls, flowers and desertscapes, it is nowhere near her best work. Over a hundred of the key pieces are at the Tate, a show that closed a few days ago, others are scattered throughout American collections. Preston is at her best with all of the iconic paintings gathered together in one spot, but sadly there are none of her relief prints, that many would argue are her most important contribution to modernism. The director of Heide, Kirsty Grant, assured me that the prints will appear in the other venues, where a space will be available for the suitable display of works on paper. The Cossington Smith selection, while possibly lacking the key Sydney Harbour Bridge painting, The Bridge in Curve at the National Gallery of Victoria, is a strong cross-section of her art with the late glowing interiors a highlight of the whole show. O’Keeffe’s famous utterance, “Men put me down as the best woman painter… I think I’m one of the best painters” applies equally to all three artists. In their respective national constructs of modernism, these artists are outstanding and key to certain developments. The final hurdle or putdown that they face is being viewed within exclusively their national constructs, especially with the Australians who have virtually no international presence or recognition. O’Keeffe has been more fortunate, as part of the Stieglitz circle she has had some early recognition and while her role may have been minimised, she was at least part of the big scene. Preston fought hard to be given recognition and used her fiery temper and her husband’s money to forge a national identity in Australia, while Cossington Smith lived quietly in Turramurra on the upper North Shore waiting to be discovered. Neither Australian artist would score even the smallest of footnotes in any account of the development of modernism internationally. This neglect is certainly not one based on the merit of their art. O’Keeffe, one of my favourite artists over many decades, in her abstracted erotic flowers, including Blue Line (1919) and the bones of the desert, such as Ram’s Head, Blue Morning Glory (1938) created an abstracted aesthetic that at times crossed over into the non-figurative. Preston, when not pursuing silly ideas concerning the creation of a ‘national art’, forged conventions of cubism onto Australian forms as in her Western Australian gum blossom (1928) and Implement blue (1927) to create strikingly original and beautiful pieces of art. Of the three, Cossington Smith was the intuitive genius, little skilled in art theory and poorly versed in art history, her quiet, inward spiritual vision developed slowly and gaining in intensity as she aged. As an exhibition there are surprising parallels in the work of the three artists, both in the formal strategies that they developed and in their strong sense of place, as they found their respective abodes in New Mexico, Mosman and Turramurra. While some may jump to the conclusion that the Australians may look stronger than their much-touted American contemporary, this is undeserved, as O’Keeffe at her best is breathtaking; this exhibition shows that she also had many ordinary days. What this exhibition demonstrates, once again, is that Australian art needs to break free from the bounds of its geography. It should be a national priority to exhibit Australian art internationally and on a regular basis. O’Keeffe, Preston and Cossington Smith: Making Modernism October 12 – February 19, 2017

Heide Museum of Modern Art, Melbourne, Queensland Art Gallery, March 11 – June 11, 2017; Art Gallery of New South Wales between July 1 – October 1, 2017 The uncanny art of Louise Hearman Louise Hearman’s win in this year’s Archibald circus catapulted the artist’s name to prominence. The win was unusual for a Melbourne artist in this most Sydneycentric of art prizes. She is only the second Melburnian to do so in the past decade; her predecessor was the Adelaide-born, Melbourne-based Sam Leach in 2010. Louise Hearman is a very Melbourne product: Melbourne-born, Melbourne-trained and Melbourne-based, but she is having her first institutional survey show at the age of 53 in the heart of the Sydney art establishment, the Museum of Contemporary Art. It is a modest-scale exhibition with about fifty smallish oil paintings on composition board (Masonite), plus about twenty-five works on paper. They are generally dark, mysterious and brooding paintings, like half-remembered nightmares, which have been lovingly distilled, recalled and depicted. They are disturbed and disturbing paintings, where surreal juxtapositioning of elements from the animate and inanimate worlds invariably haunts the imagination of the viewer. Franz Philipp when discussing the small wartime paintings of Arthur Boyd described them as ‘agoraphobic surrealism’ and there is something of that quality in Hearman’s art, with carefully observed images brought in from the outside world and then deciphered and dissected like specimens within her studio space. Hearman seduces us with her immaculate technique, whether it be capturing light on a child’s face and hair, a drop of water, a flower petal or animal fur, details in a landscape or textures on disparate surfaces. She certainly has mastery of the painter’s toolbox, but also is quick to reject a photographic verisimilitude and frequently hastens to add passages of textured paint and unfinished edges to stress the fact that we are dealing with a tactile painting that carries a human touch and not a mechanical image. Hearman’s art sits uncomfortably within the general realm of the uncanny. Sigmund Freud in part reformulated and popularised the concept of the uncanny early in the 20th century and it received further refinement in the writings of Julia Kristeva and other theorists. The uncanny has become the subject of numerous art exhibitions with the famous examples at the Tate Liverpool in 2004 and at the Walker Art Center in 2012. Freud’s pronouncement that “the uncanny was not to be found in the exotic but the everyday” is a good starting point for the consideration of Hearman’s imagery, where she scavenges the everyday to create her highly disturbing compositions. Most of her work is untitled, so there is no authoritative guide on how we are meant to ‘read’ the imagery. The objects are highly recognisable – a child’s head, a cat, a dog, a row of teeth or luminous skies – but this set of obsessive images has been transformed through its setting. The compositions are situational, rather than descriptive, like a child half-submerged in water in what appears to be an industrial landscape, a child confronting the head of a serpent or the head of a dog set within the centre of a flower, but the meaning or purpose of these situations is undefined. They are lovingly, immaculately and exactingly depicted, but remain hauntingly enigmatic. Even when her paintings are of a recognisable subject, such as that of her partner Bill Henson, for which she was awarded the Doug Moran National Portrait Prize for 2014, the treatment of the subject as if it is a still life and a study of light on surfaces, rather than an animated human head, produces something of a distancing effect as we fail to emotionally engage with the subject.

Despite the implied dynamism in a number of the compositions, there is a distilled sense of stillness in her paintings, as if frozen in the moment. The sense of anticipation is immense, where so much could happen, but in fact very little does, and we are called upon to complete the narrative in our imagination. The exhibition in Sydney is an uneven show, in places repetitive, while in others somewhat disjointed. Hearman emerges from it as a very strong draughtsman and a skilled technician. While working within a tradition of art history, where predecessors include Goya, the Surrealists and Hans Bellmer and her fellow travellers are the artists of the uncanny, she has developed her own and distinctive voice in her small painted vignettes. While many artists seem to require a huge scale to make a trite comment – an anecdotal one-liner – Louise Hearman conveys effectively her internalised scream in an intimate easel painting. Louise Hearman September 29 – December 04, 2016 Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, no admission charge Does Australia really need another art blog? I don’t know, but I increasingly feel that I need a platform for writing art criticism – one that I control and that is not at the whim of newspaper and magazine editors.

When I realise that the first art critique that I published was forty years ago, I do feel like a fossil, one who wrote before computers or the Internet and at the time when the intrusiveness of spellcheck belonged to the realm of science fiction devoted to accounts of totalitarian regimes. Back then, it was just you and the art that you tried to explain and evaluate for your audience. I estimate that I have published over 3,000 art crits over all of these years and perhaps it is timely to take stock and reflect. For me, art criticism always has both an exegetical and judicial function: you seek to explain, interpret and at times recreate or describe an art object, exhibition or art experience, as well as evaluate it and place it within a broader context of art history. In some ways, in the past decade or so, there has generally prevailed an era of politeness in Australian art criticism, where the regurgitation of institutional media releases passes for art criticism and art critics tread ever so carefully so as not to offend potential sponsors or other interested parties. In the trade it is known as being ‘streetwise’. Perhaps we need a little bit more grit and vulgarity in our art criticism and words such as foolish, vacuous, self-indulgent and trite could be reintroduced into our lexicon, while terms including stunning, once in a lifetime, cutting edge and cute should be banned or at least treated with considerable caution. Technology has completely re-shaped the writing of art criticism and the freedom of a blog, with its endless potential for links and illustrations frees us from the shackles that constrained the pioneers of art criticism and such luminaries as Denis Diderot, Charles Baudelaire and John Ruskin. There is little need for tedious descriptions of what we can now view in crisp, high-resolution colour reproductions. We have long suffered art criticism that has adopted an ethical stance or promoted the phoney analysis of formalism or has employed the art under question for a personal agenda or a construct of social and political theories. A blog has the potential for greater immediacy and transparency. The readers can immediately see for themselves what is being discussed and assess the veracity of the claims being made. There are fewer constraints on space, fewer dictates from formatting and no consideration of sponsorship. While ten years ago we could still argue that access to a computer and the Internet was restricted to a minority, in the second decade of the 21st century it is the domain of the majority. It is also democratic, or at least this blog will be, with free and unimpeded access. You don’t have to buy a magazine, purchase access or special software, simply read what you want to read and for how long you want to read it. For any writer, the size and calibre of readership is always a challenge and I have little idea if the audience for GAB will be a small circle of friends or a broader art public. In a way, this does not really matter: what is more important is that you can give voice to ideas that are close to your heart. Whether they fall on fertile or barren ground is all a question of perception. Sasha Grishin 1 November 2016 |

GRISHIN'S ART BLOG

Sasha Grishin AM, FAHA is the author of more than 25 books on art, including Australian Art: A History, and has served as the art critic for The Canberra Times for forty years. He is an Emeritus Professor at the Australian National University, Canberra; Guest Curator at the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne; and Honorary Principal Fellow, Faculty of Arts, at the University of Melbourne. Archives

September 2023

Categories

Keep up-to-date with Sasha Grishin's blog with the RSS feed.

RSS offers ease of access and ensures your privacy, as you do not need to subscribe with an email address. Click here to download a free feed reader |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed