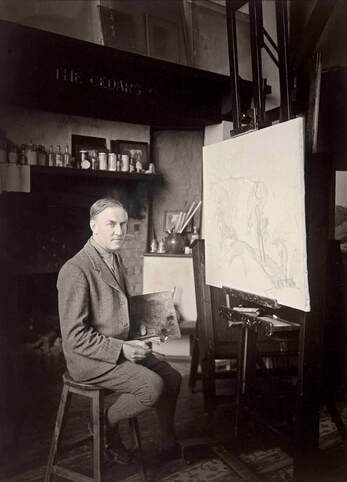

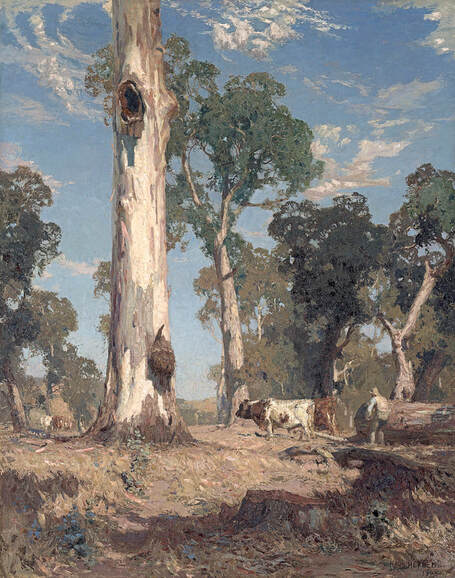

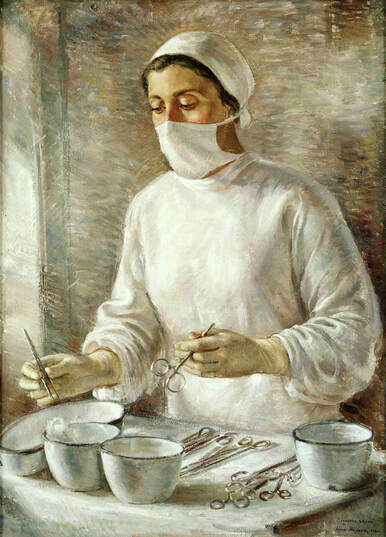

The Heysens: Harmony and discord Although Hans and Nora Heysen were blessed with longevity, both living into their nineties, their artistic careers followed markedly different trajectories. Hans Heysen (1877-1968) was an evergreen favourite artist with the general public through his gum tree portraits, images of pastoral arcadia and of the quintessential Australian landscape, while his daughter Nora Heysen (1911-2003) had a career studded with early highlights, but one which subsequently petered out into genteel obscurity. Hans Heysen is, in many ways, an atypical landscape painter in the Australian context, one who did not emerge out of the glowing green and gold formula of the Heidelberg School and the various diluted versions of impressionism. He was born in Hamburg in Germany on 8 October 1877 and emigrated to South Australia as a child with his family in 1884. Between 1893-94, Hans studied watercolour painting in James Ashton’s ‘Norwood Art School’ in Adelaide and by 1898 he was at the South Australian School of Design. In the following year, supported by four private local patrons, he went to Europe for four years, spending two-and-a-half years in the different Académies in Paris, and then visited Holland, Britain, Germany and Italy. Shortly after his return to Australia, Hans painted the large and majestic oil painting, Mystic Morn, 1904, for which he was awarded the Wynne Prize for landscape art by the Art Gallery of New South Wales trustees. When it was exhibited in the seventh Federal Exhibition in Adelaide, it was promptly acquired by the Art Gallery of South Australia, their first acquisition of his work. Heysen worked on sketches for this painting near Meadows in the Adelaide Hills during Easter in 1904 and painstakingly executed the work in his city studio on the large four-foot by six-foot format (122.8 x 184.3 cm). The picture to a large extent reflects European Symbolism, both in the poetic symbolic allusions of its title and in the symbolic golden light that imbues the landscape. It also betrays traces of Art Nouveau in the sinuous line of the saplings in the foreground floating over the silhouetted background gums reminiscent of those encountered in Sydney Long’s art. Long may have had this in mind when he commented in 1905, in reference to Mystic Morn, “The gum trees are there, but the feeling is not Australian. The Australian feeling is not to be got by sticking in a gum tree.” For all of its inherent nationalism, it is interesting to note that in this painting, and in virtually all of Heysen’s oeuvre, it is cattle and other domestic farm animals that dwell in the Australian bush, as in European Barbizon art, rather than kangaroos or other native animals. Later in 1904, Heysen married Selma (Sallie) née Bartels and following several financially very successful exhibitions, the Heysens bought in 1912 the thirty-six-acre property, The Cedars, near Hahndorf, an area settled by German migrants, where he was to remain until his death in 1968. Hans Heysen was an artist whose reputation has suffered through his popularity and the amateur imitators who churned out acres of poorly executed gum tree paintings in the Heysen style. While Heysen did become, in Herbert Badham’s words, “the portraitist of the gum-tree” which became like a patent in his art, his art was based on very solid workmanship with a firsthand knowledge of developments in European art. Despite the overt nationalism detected in his pictures, during the First World War when the anti-German sentiment in Australia reached its xenophobic peak, the Trustees of the Art Gallery of New South Wales refused to include Heysen’s work in a Loan Exhibition of Australian Art until he “definitely and satisfactorily” declared that his “allegiance and sympathies are with the British Nation”. Heysen was offended and declined to make such a declaration and was not included in the exhibition. As he explained in a letter to Elioth Gruner, “I … am sorry at not being represented but as I dislike the approach of the Gallery Board on the question of nationality I must take the consequences of what I thought right to stick up for – if a man’s feeling for Australia cannot be judged by the work he has done – then no explanation on his part would dispel the mistrust.” It is a curious irony that an artist who defined a particular nationalist vision of the Australian landscape within the context of Federation experienced some persecution as a German migrant but he continued to live in the mainly German enclave of Hahndorf and at the age of ninety, at his own request, was buried at the Hahndorf cemetery by a pastor of the Lutheran Church. Nora Heysen was the fourth of Hans and Selma Heysen’s eight children and was born at The Cedars in Hahndorf in South Australia in 1911. Having a famous artist as a father was a mixed blessing, where there was both an encouragement in art, as well as a degree of interference. Nora recalls, “one day I left a painting of a basket of eggs in the studio – which I thought was pretty good – but when I got back I found Father had drawn squares all over it showing where my draughtsmanship was wrong. I was furious. Of course he was right, but it took me a long time to see it ...” Study in Adelaide was supplemented with tuition at the Central School in London under Bernard Meninsky. Nora spent three years in Europe, between 1934 and 1937, sharing her flat and her excursions to Paris and the art galleries of Britain with a sculptor from Adelaide, Everton (Evie) Stokes. After spending some months back at The Cedars, in 1938 she shifted to Sydney where she would remain for the rest of her life. That year she was awarded the Archibald Prize for an accomplished but ultimately conventional portrait of Madame Elink Schuurman, the first woman to be awarded the prize. Five years later, in October 1943, Nora was appointed as an Australian official war artist, the first woman to receive this appointment, and spent some time in New Guinea where she met her future husband, Dr Robert Black, In 1954, Nora and Black moved to The Chalet in Hunters Hill, in Sydney remaining there till her death in 2003. Although both through family connections and the Archibald Prize Nora Heysen had established a profile in Adelaide and Sydney, it was only quite late in her career that her work received serious attention. In 1989, when she was seventy-eight years old, a retrospective exhibition of her work was held in Sydney which revealed the full scope of her talent with strong introspective self-portraits, vibrant flower pieces and meditative still life compositions. Throughout her life, Nora was haunted by the uncertainty of her identity as an artist – her individuality as opposed to being the daughter of a great artist. When she was in her fifties and interviewed by the press, the article was published under the title “I don’t know if I exist in my own right.” It appears that only late in life Nora was recognised for her own art and acclaimed by the broader art community as an artist of considerable standing, quite independent of being the daughter of Hans Heysen. Hans and Nora Heysen: Two generations of Australian art National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, March 8 – July 28, 2019

1 Comment

|

GRISHIN'S ART BLOG

Sasha Grishin AM, FAHA is the author of more than 25 books on art, including Australian Art: A History, and has served as the art critic for The Canberra Times for forty years. He is an Emeritus Professor at the Australian National University, Canberra; Guest Curator at the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne; and Honorary Principal Fellow, Faculty of Arts, at the University of Melbourne. Archives

September 2023

Categories

Keep up-to-date with Sasha Grishin's blog with the RSS feed.

RSS offers ease of access and ensures your privacy, as you do not need to subscribe with an email address. Click here to download a free feed reader |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed