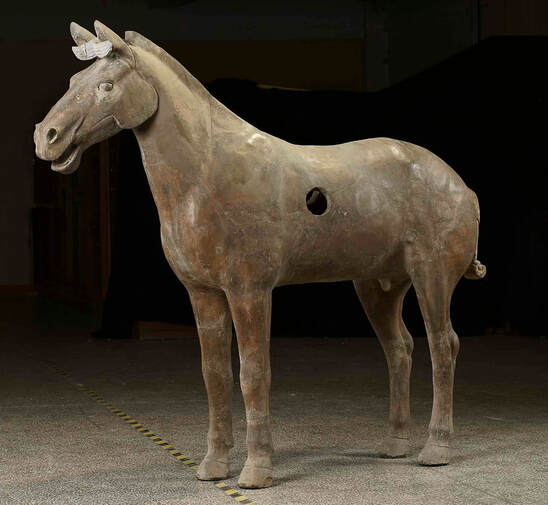

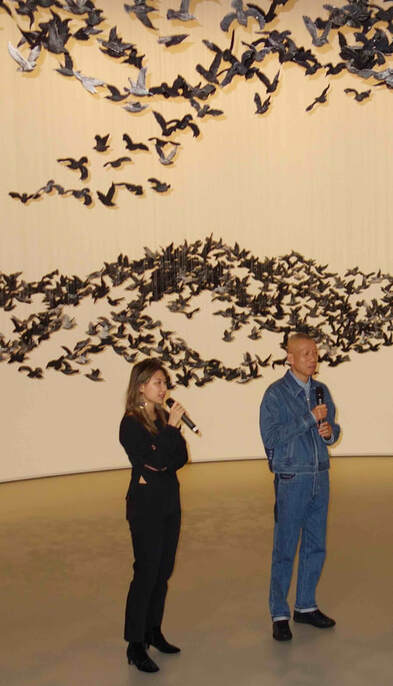

Terracotta Warriors & Cai Guo-Qiang: A contemporary perspective on ancient history Since they were first uncovered in 1974, the thousands of Terracotta Warriors guarding the afterlife of Qin Shi Huang (259-210BC), the first Qin Emperor of China, have been on the move advancing the political, cultural and artistic policies of the Peoples’ Republic of China. The mausoleum of Qin Shi Huang in Lintong County, outside Xi’an in Shaanxi province, China, about thirty-five metres underground, is a very popular tourist site and presently attracts about 30,000 visitors a day. In all, it is estimated that there are about 8,000 warriors, 130 chariots, 520 horses, 150 cavalry horses and other pits containing non-military figures, including court officials, acrobats, performers, bureaucrats and musicians. Only a fraction of this huge figurine group has been fully excavated. Despite the romantic theory that each figure is unique and individualised, there were a number of casts – for example, ten basic face types – and many of these were manipulated slightly while the clay was still wet. The figures were assembled from a limited number of stock parts to create the impression of a huge differentiated army. The figures are hieratic – a general tallest at 196cm, others a bit smaller – and vary in uniform and hairstyle in accordance with rank. There was also a variety of poses. Originally the figures were polychrome – pink, red, green, blue, black, brown, white and lilac – and they held real weapons. On exposure to air, the colours quickly faded and the weapons powdered away leaving only fragments. Excavations are paused until conservation techniques can be refined to preserve the original appearance of the work. Emperor Qin Shi Huang was a cruel despot obsessed with power, the burning of books and megalomania, with an estimated 700,000 workers labouring on his tomb. Nevertheless, he introduced many legal, monetary and language reforms and commenced the building of the Great Wall. On his death many of the labourers, concubines and the emperor’s inner circle were incarcerated and perished in the tyrant’s tomb to seal the secret of its location. His dynasty was short-lived and his successors of the Han Dynasty turned their backs on many of his excesses, but retained a number of the key reforms. The first time these archaeological artefacts toured overseas was in 1982 and it was to the National Gallery of Victoria and then onto the Art Gallery of New South Wales. Subsequently they have marched all around the world, in many places attracting record crowds only to be rivalled by the archaeological exhibit of King Tutankhamun from Ancient Egypt. They were also shown again in Australia at the Art Gallery of New South Wales in 2011. The Chinese state carefully controls the exposure of the terracotta warriors abroad, with each venue allowed only ten figures – the British Museum in 2007 was the exception with twelve figures. The National Gallery of Victoria has selected eight warriors in a variety of poses, plus two beautifully articulated horses. The genius of the Melbourne display lies not in terracotta warriors, shown in their mirror cases, nor even the 160 archaeological objects drawn from museums across the Shaanxi province (that in many instances are more interesting than the restored terracotta figures), but the juxtapositioning of the ancient art with the contemporary vision of Cai Guo-Qiang. Cai, born 1957 and since 1995 largely based in New York, in many ways presents a lyrical, contemplative and humanist alternative to the brutalist art of Emperor Qin Shi Huang. The emperor sought to dominate the environment through a show of power and force: Cai reapproaches the environment surrounding the tomb – the soil, the flowers, trees and the fauna – that ultimately seem to dominate even the emperor’s wish for immortality. The leitmotif throughout Cai’s commentary on the ancient art is the starling – a bird found in the region of the tomb. Cai has created a great swarm of ten thousand suspended blackened porcelain starlings that appear from a distance almost like a traditional Chinese ink landscape painting. It is something like the souls of the perished entombed under the ground. Cai observes, “The ever-changing formation of 10,000 porcelain birds seems to embody the lingering spirits of the underground army, or perhaps the haunting shadow of China’s imperial past. But in this age of globalisation, aren’t they also forming a mirage, an exoticised imagination of the cultural other?” Peonies and cypress trees, which grow in the area, are celebrated in porcelain constructions as well as in vast gunpowder drawings. Whereas the imperial art was ridged and disciplined, gunpowder drawings on silk and paper invariably involve the element of chance and unpredictability. Forms emerge darkly, recognisable, but as if seen from a great distance. Through the use of materials associated with China – porcelain, silk, paper and gunpowder – Cai reverts to tradition to make an unexpected commentary on antiquity that is ever-present and reasserting its power. This is a complex, powerful and absorbing exhibition, where through the unexpected intervention of a contemporary artist, ancient forms are given a new life and a new meaning. Melbourne Winter Masterpieces: Terracotta Warriors & Cai Guo-Qiang, National Gallery of Victoria, International, 24 May-13 October 2019

1 Comment

6/6/2019 16:31:38

Thank you for making that comparison and your thoughts public as you do so well. I am looking forward to reading more of your blogs.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

GRISHIN'S ART BLOG

Sasha Grishin AM, FAHA is the author of more than 25 books on art, including Australian Art: A History, and has served as the art critic for The Canberra Times for forty years. He is an Emeritus Professor at the Australian National University, Canberra; Guest Curator at the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne; and Honorary Principal Fellow, Faculty of Arts, at the University of Melbourne. Archives

June 2024

Categories

Keep up-to-date with Sasha Grishin's blog with the RSS feed.

RSS offers ease of access and ensures your privacy, as you do not need to subscribe with an email address. Click here to download a free feed reader |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed