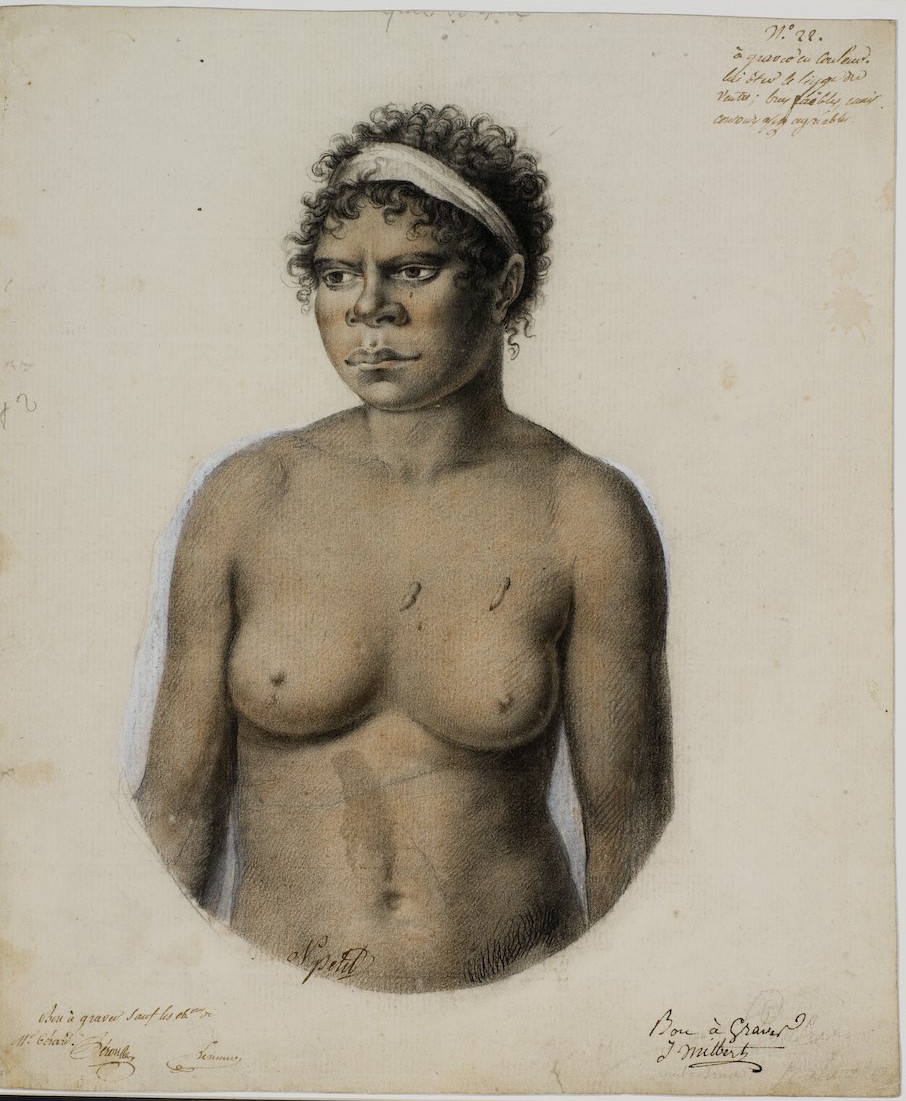

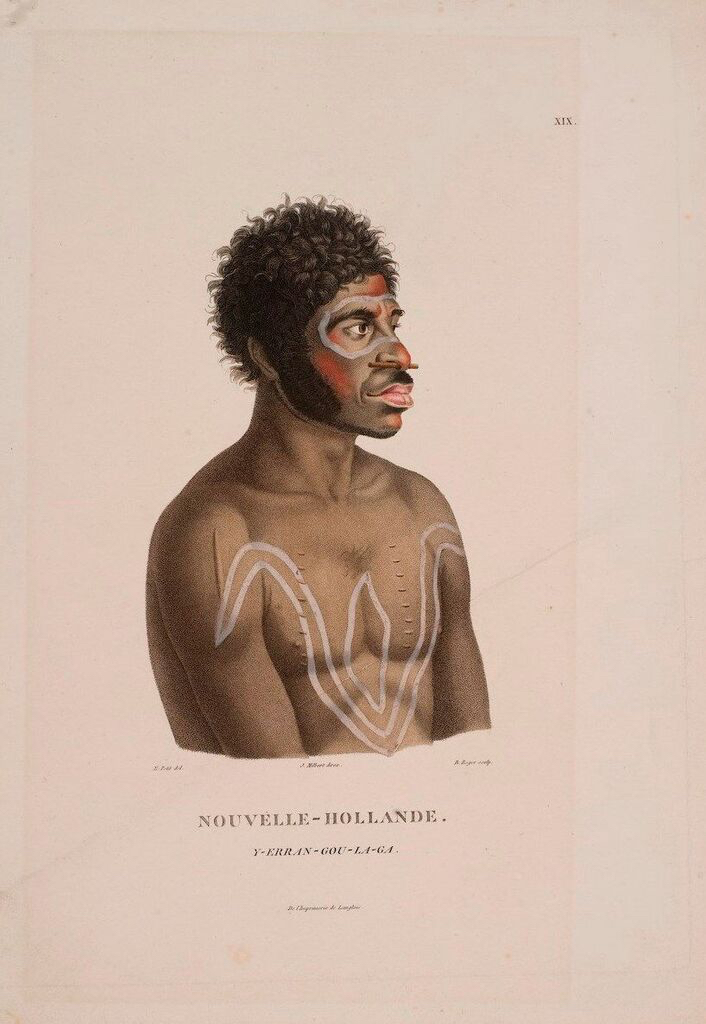

The French Connection in Australian art Long before Brexit the British and the French were rivals both in Europe and beyond. As colonial powers, Britain and France flexed their considerable naval muscle in establishing new colonies and trade routes, frequently within the spirit of hostile competition. The rise of Napoleon Bonaparte was generally viewed by the British with derision, as “the little corporal who built an Empire”, a type of Donald Trump of his time, who set out to disrupt British trade routes and colonial prosperity. The battle for colonial domination was fought out as far away as Australia and while the story of Captain Cook and the First Fleet is known to every school child, the French adventure is almost completely ignored. An exhibition devoted to the voyages of Nicolas Thomas Baudin to Australia from 1800 to 1804 has opened at the South Australian Maritime Museum in Port Adelaide before embarking on a two year national tour that will take the exhibition to Tasmania, Sydney, Canberra and Perth. As with Cook’s journey some three decades earlier, Baudin’s epic voyage answered to a number of different agendas in his home country, including political, economic and cultural. Citizen Baudin, as a patriotic Frenchman eager to serve the Republic, had already proposed to the French navy schemes to disrupt British trade and had earlier been frustrated by British authorities in Trinidad who had prevented him from reclaiming his possessions. In April 1800, the First Consul, Napoleon Bonaparte, personally signed a decree to fund and send Baudin as commander in charge of an expedition to explore New Holland and Van Diemen’s Land. Baudin, the Commander-in-Chief of the corvettes Géographe and Naturaliste, and his artists Charles-Alexandre Lesueur and Nicolas-Martin Petit, made their way to Australia. Lesueur and Petit, could be described as ‘accidental artists’, who were nominally appointed as ‘assistant gunners’ for the expedition, but once the three official artists absconded to the Île de France (Mauritius) in April 1801, six months into this epic journey that was to last three and a half years, they became the official pictorial chroniclers for the expedition. The survivors of the expedition returned to France in March 1804 and, three years later, the naturalist François Péron and Lesueur steered to fruition the publication of the first volume of the atlas Voyage de découvertes aux terres australes with forty-one lavish plates. Whereas British authorities frequently tightly control loans to the colonies, for example, scarcely more than half of the original History of the world in 100 objects exhibition left the British Museum to come to Australia in its original form, the French authorities said “oui” to pretty well everything. There are about 340 precious paintings and drawings from the Museum of Natural History in Le Havre, where most of the Baudin Australian material is housed; unique objects including Baudin’s chronometer; the original hand drawn maps and a most unexpected treasure, Baudin’s personal illustrated journal from the National Archives of France. Together with the other colonial powers, the French artists subscribed to the theory that by classifying and naming that which they encountered in the new world that lay beyond the pillars of Hercules, they would own it. The images of flora and fauna are initially sketched and observed with greatest fidelity to actual appearances, then they are classified to the most exacting categories of the Linnaean system and subsequently some are selected to be engraved, where they are subjected to the prevailing tastes in animal and botanical art of the period. While making my way around the exhibition, it became a sobering experience to see, time and time again, species that existed in Australia for thousands of years that were recorded by Europeans for the first time 200 years ago, now declared extinct because of the impact of these same Europeans. When it came to the depiction of Indigenous Australians, in contrast with the English colonists, Baudin’s artists seemed conscious of the values of “liberté et égalité” and left some of most empathetic images in first contact art. There was no perceived need to conqueror or ridicule, but simply to record and to testify to their existence. Attempts were made to write musical notation to local chants and possibly Indigenous people were invited to make their own drawings on the materials provided by the French travellers. All of these precious documents are included in the exhibition. Baudin never returned to France, but died on the return journey on 16 September 1803 on the Île de France and much of his heritage has remained neglected until recent times. Nevertheless, one may pause to ponder, what would have happened if the French had settled in Australia instead of the British or if they had established a colony in Australia as had been speculated in France and suspected by the British. English authorities constantly pre-empted the French, planting the Union Jack at every opportunity to announce that the land was no longer vacant and that the welcome mat had been removed. Exhibition Itinerary

South Australian Maritime Museum: 30 June – 11 December 2016 Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery: 7 January – 20 March 2017 Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery: 7 April– 9 July 2017 Australian National Maritime Museum: 31 August – 26 November 2017 National Museum of Australia, Canberra: 15 March – 11 June 2018 Western Australian Museum: September-December 2018

4 Comments

28/11/2016 09:03:25

sasha, thanks for this.I first became aware of Baudin and his fate in 2002 when the SA Art Gallery hosted a conference and exhibition "First Encounter " to mark the meeting in 1802 of Flinders and Baudin at what is now called Encounter Bay .For your readers who might be interested ,I recommend "Ill-Starred Capitans -Flinders and Baudin by Anthony J Brown.

Reply

Pippa Lightfoot

28/11/2016 11:28:05

Interestingly these, like Cook are really quite well known... but the first specimens from Australia were collected on the West coast much earlier by Vlamingh 1697.

Reply

Liz Clemons

29/11/2016 20:52:29

One such placement of the Union Jack was in Sea Elephant Bay on King Island on Dec 14th 2002. The story surrounding it is entertaining and prophetic.

Reply

13/9/2018 03:33:28

I’m impressed, I must say. Really rarely do I encounter a blog that’s both educative and let me tell you, you have hit the nail on the head. The issue is something that not enough people are speaking intelligently about. I am very happy that I stumbled across this in my search for something relating to this.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

GRISHIN'S ART BLOG

Sasha Grishin AM, FAHA is the author of more than 25 books on art, including Australian Art: A History, and has served as the art critic for The Canberra Times for forty years. He is an Emeritus Professor at the Australian National University, Canberra; Guest Curator at the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne; and Honorary Principal Fellow, Faculty of Arts, at the University of Melbourne. Archives

June 2024

Categories

Keep up-to-date with Sasha Grishin's blog with the RSS feed.

RSS offers ease of access and ensures your privacy, as you do not need to subscribe with an email address. Click here to download a free feed reader |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed