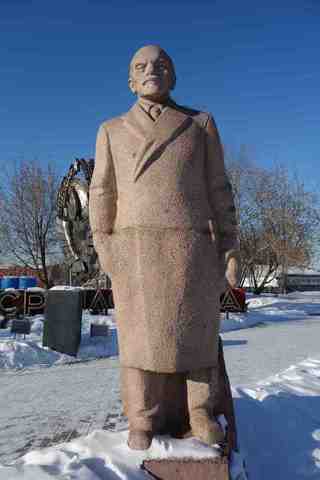

Recognising one’s cultural heritage Should good art be destroyed if it depicts bad politics? Leonardo da Vinci’s single most significant commission was an equestrian sculpture for the Milanese despot, Duke of Milan Ludovico il Moro (Ludovico Maria Sforza), that of his father Francesco mounted on horseback. It was to be the largest equestrian sculpture in the world, but when the French captured Milan, Leonardo’s model was promptly destroyed. Ludovico’s other major commission from Leonardo was the Last Supper in Milan, which fared better until bombed by the Americans in WWII. Another major category of art destruction comes with regime change. When the French Revolution brought to a close a despotic regime, the royal abbey of St Denis in Paris was desecrated, the façade sculptures smashed,and palaces ransacked. The remains are now cherished and the subject of major blockbuster exhibitions. What about art from the more recent past? I remember being quite shocked when the German artist Jörg Immendorff said to me that Germany should establish a special museum of the art of the Third Reich. His argument was that historical amnesia was a poor policy and one must acknowledge the past, shine a light on it, and not hide it, as in dark places seeds of evil and falsehood breed. In retrospect there was much merit to his idea. Over the past few years I have made it a habit of popping in on Russia on my way back to Australia from Europe or the States. The Russian art scene is one of the most interesting and vibrant in the world and about a dozen major museums of modern and contemporary art exist in Moscow alone. The Garage Museum of Contemporary Art in Gorky Park is a fairly recent and spectacular addition. However the phenomenon that I have been particularly fascinated by is Russia’s treatment of the unpopular regimes of the past. Following the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, the autocratic tsars were overthrown, the palaces and the manor houses of the nobility ransacked and frequently destroyed and the symbols of the old regime reviled. Today, anything with tsarist insignia on it is worth serious money and the old palaces are lovingly restored and serve as major tourist magnets for Russian and foreign visitors. The Gorki Leninskiye estate, on the outskirts of Moscow, was the official country residence of the Morozovs (best known for their fabulous art collection) and has been preserved in its original form through a peculiar quirk of circumstance. After the revolution, it became Lenin’s country dacha, after he was shot in an assassination attempt, and finding the place too grand to occupy, he ordered for the furniture to be covered up and nothing altered while he lived in humble surroundings in part of the estate. Following his death in 1924, it became holy ground, so that even Stalin did not dare to touch it. So it remains today – the estate is preserved as the Morozovs left it, while in an outer building, some 800 metres away, are Lenin’s study and quarters transferred from the Kremlin and a goodly distance away, out of view of the manor house, is the rather grand Lenin museum - a relic from the 1980s and the final years of Soviet power. After Nikita Khrushchev denounced Stalin’s personality cult in 1956, Stalin’s statues quietly vanished (except in his homeland in Georgia) and were never to reappear. Stalin was as much as possible airbrushed out of Soviet history as Hitler had vanished from German history after 1945. After the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, many of the Soviet sculptures were toppled and Socialist Realist art became a term of abuse. Although this is all very understandable, it is an act of falsification and frankly one has to argue that some of the monumental Soviet Socialist Realist art was quite good, technically accomplished and was created by some of the best artists of the day. To pretend it simply did not exist or that everything that existed in the Soviet Union was simply bad, is an act of falsification. It is a sign of a country’s maturity to come to grips with its past – not to hide it or disguise it, but to acknowledge its historic existence, criticise its excesses and weaknesses but to respect its achievements. In this context I was delighted to see in the region of the new Tretyakov Gallery of Modern Art in central Moscow, the Muzeon Sculpture Park and Exhibition Space , which includes a display of Soviet monumental sculptures that have been brought down throughout Moscow following the fall of the Soviet Union. This includes the monumental sculpture of Felix Dzerzhinskiy, the founder of the Soviet security services, a huge sculpture of the great writer Maxim Gorky, several statues of Lenin, a couple of Brezhnev statues and a series of monumental works celebrating the Soviet Union. Juxtaposed with these are monuments to those who perished in the Gulags, including the imposing work by E.I. Chubarov titled a monument to the Victims of the Totalitarian Regime, 1980s, made of granite and metal. It is a sign of cultural, political and spiritual maturity when a country can acknowledge its past and be not afraid of the future. The tradition of Russian art not only includes the great iconic heritage, the avant-garde, with masters like Kazimir Malevich, Wassily Kandinsky and Marc Chagall, as well as contemporary conceptual artists including Ilya Kabakov and Erik Bulatov, but also the Soviet period with monumental sculptors including Vera Mukhina and Sergei Merkurov who now have their own little corner in Russian art history. Russophobia that has been a feature of recent American politics has had little impact on the Russian economy – the shops are full of produce, people are well dressed and teched up with the most modern gadgetry, but there is a growing mood of reflectiveness as Russia develops a more rounded and mature attitude to its cultural history and is gradually asserting its place as one of the major forces in contemporary art.

4 Comments

David Handley

9/2/2017 07:41:46

Thank you Sasha. As always a thought provoking read, while making one want to venture to Russia.

Reply

jane cush

9/2/2017 08:47:22

Great read thanks Sasha.

Reply

20/2/2017 16:33:10

is that the armour you wore after your book on Australian artwas published..very timely piece on monumental art.

Reply

Sasha Grishin

20/2/2017 17:32:21

Dear Garry, Heavens no! That suit of armour is now completely battered and bloodied and cannot be worn in public, This is a 'new' suit on loan from the Historical Museum in Moscow on the Red Square. Provided I am only reflected in the glass darkly, it remains quite safe.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

GRISHIN'S ART BLOG

Sasha Grishin AM, FAHA is the author of more than 25 books on art, including Australian Art: A History, and has served as the art critic for The Canberra Times for forty years. He is an Emeritus Professor at the Australian National University, Canberra; Guest Curator at the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne; and Honorary Principal Fellow, Faculty of Arts, at the University of Melbourne. Archives

June 2024

Categories

Keep up-to-date with Sasha Grishin's blog with the RSS feed.

RSS offers ease of access and ensures your privacy, as you do not need to subscribe with an email address. Click here to download a free feed reader |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed