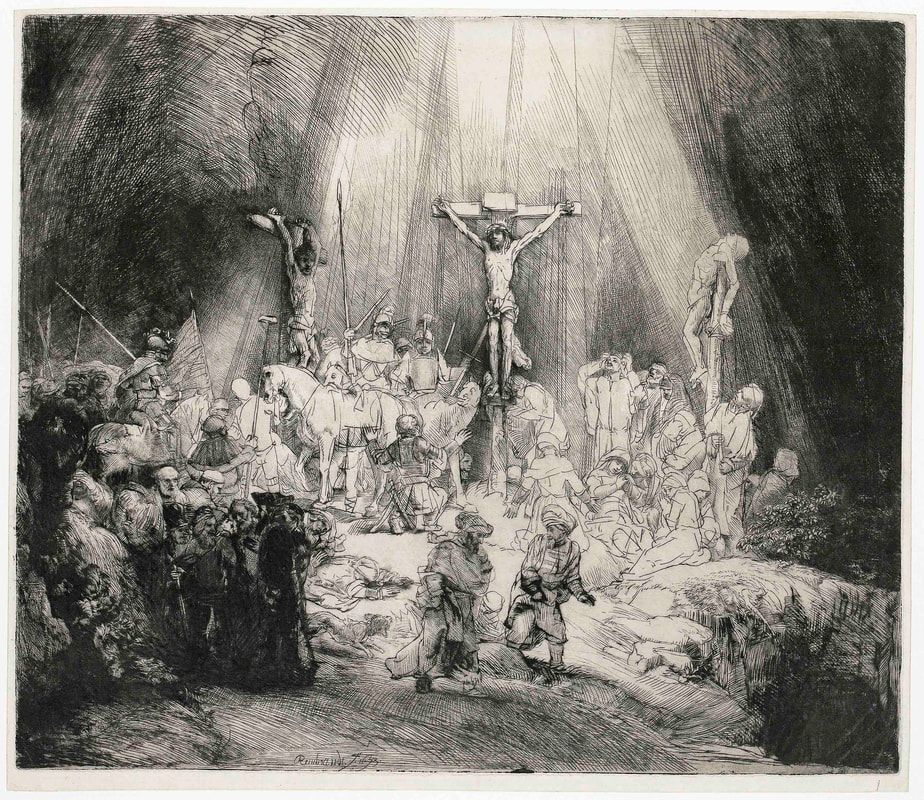

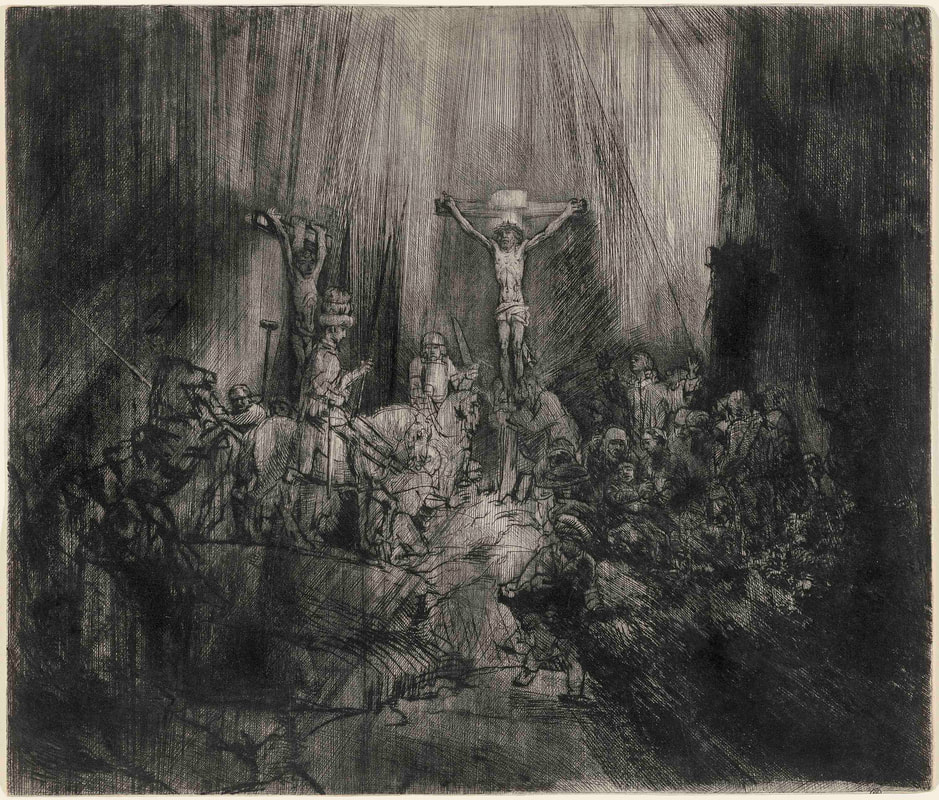

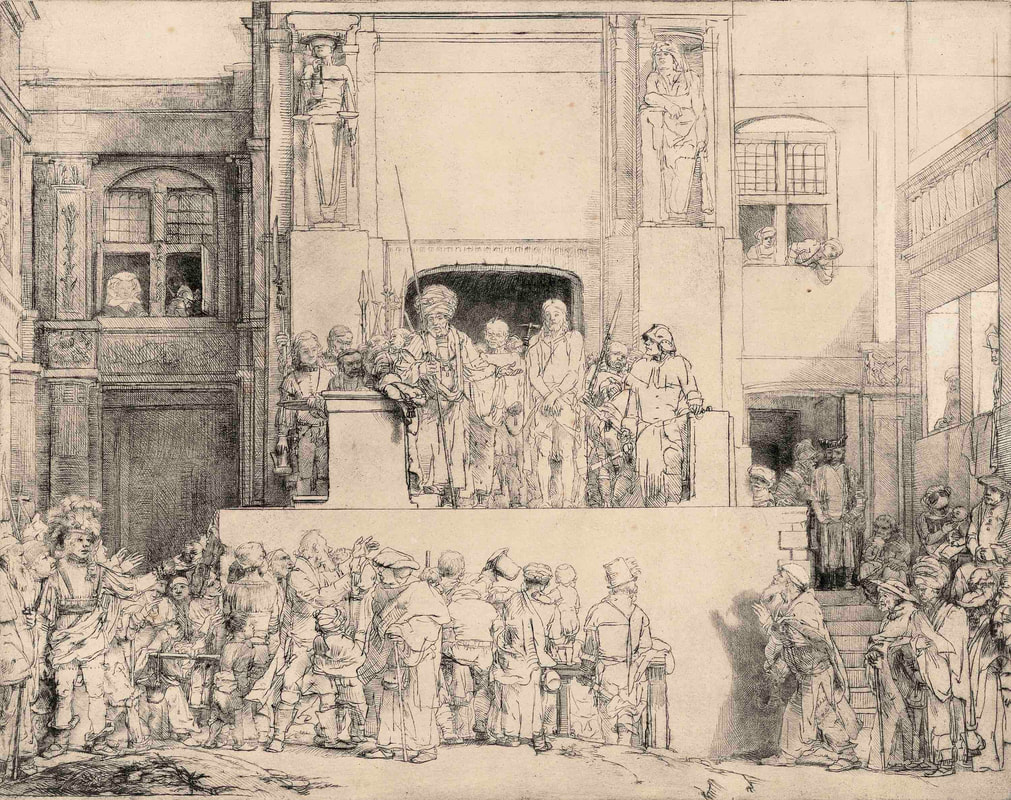

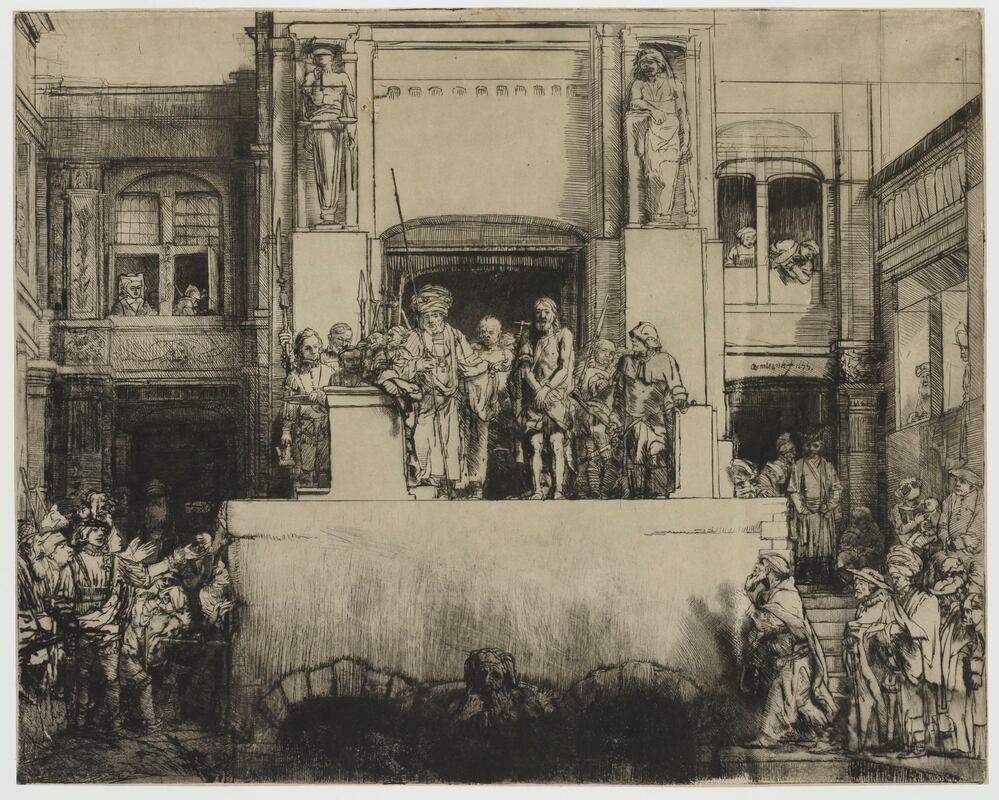

Rembrandt: True to Life Few would dispute that Rembrandt is one of the greatest artists in the Western tradition of art. His wonderful oil paintings, The Jewish Bride, The Night Watch and some of the superlative self-portraits are amongst the gems that illuminate any traditional account of art history. What is less well-known is that Rembrandt was an outstanding printmaker, arguably the greatest etcher of all time. Some would argue that perhaps Rembrandt’s greatest contribution to art was not as a painter, but as a printmaker. As a young art history student in Melbourne, I had the privilege of taking Ursula Hoff’s course on Rembrandt and she, as the Keeper of Prints and Drawings at the National Gallery of Victoria, had an unrivalled knowledge of Rembrandt and was partly responsible for building up one of the greatest collections of Rembrandt’s etchings anywhere in the world. This exhibition, Rembrandt: True to Life at the NGV brings together about 100 prints from the gallery’s collection with significant loans of paintings, prints and drawings from the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC, the Louvre Museum in Paris, the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, and the Teylers Museum in Haarlem. It is a brilliant exhibition that is worthy of the trip to the NGV and although physically it is a discreet show – it is intense and focused – it will require several hours of inspired viewing. What was it about Rembrandt that made him into such a brilliant etcher? He made over 300 etchings and drypoints, so seeing about a third of his print oeuvre at this exhibition, accompanied by some of his drawings, oil paintings and contextual pieces, makes this into a significant Rembrandt show by international standards. In the 17th century, many of Rembrandt’s contemporaries, including Peter Paul Rubens, made some of their money through reproductive engravings and etchings of their paintings. Rembrandt, after a couple of early failed attempts, realised that he was incapable of copying himself, and for him painting and printmaking ran as parallel but separate streams of creativity. What he attempted in painting, he did not repeat in etching, and some of his greatest achievements in his etchings, he did not attempt in his paintings. In other words, Rembrandt realised that painting and etching had their own unique pictorial languages, and one should not attempt to do in painting something that is unique in etching. There are no bad Rembrandt etchings and each work in this exhibition calls for special discussion. Rather than presenting a chronological survey and pausing on the tragic circumstances of the artist’s life, I mention a few prints that I truly love. Rembrandt’s Christ with the sick around Him, (The hundred guilder print) c 1648, an etching with drypoint on Japanese paper, is one of his most celebrated works. People who are given to hyperbole describe it as his equivalent in printmaking to his Night watch in painting, while the popular title, the 100 guilder print, in part refers to a literary tradition that Rembrandt had to buy back a copy of this print for this huge sum of money, and in part refers to the difficulty in identifying the subject matter. This is Rembrandt’s most ambitious religious composition in any medium and one on which he worked for several years. The literary source appears to be the Gospel according to St Matthew, chapter 19, where he married together several episodes. On the right-hand-side of the etching is the reference to the great multitudes who followed Christ and “he healed them”. On the far left are the Pharisees who tempted Christ to condemn divorce, with two mothers bringing their children to Christ to be blessed and when the apostles try to restrain them, Jesus rebukes them “Suffer little children, and forbid them not, for such is the kingdom of heaven.” Between the two mothers we see the pondering figure of the rich young man who wishes for eternal life, but who is troubled by the thought that he must sell all his possessions and give them to the poor. This may explain the strange image on the right of the camel in the gateway that it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than it is for a rich man to enter the Kingdom of God. The chapter in the Gospel ends with the words: “many that are first shall be last, and the last shall be first” and in Rembrandt’s etching the humble and the afflicted are visually dominant over the rich and the powerful. Rembrandt worked on this composition over several years with preparatory drawings dating from 1639 to 1649. Despite the studies, the final resolution of the print Rembrandt worked out on the plate itself and numerous scholars have noted the changes and trace elements of earlier impressions. Christopher White in his masterly analysis of this print in the two-volume publication Rembrandt the etcher notes: “Rembrandt, having bitten the plate at least twice to obtain a contrast in tone, went to work directly on the plate. The figures of the Pharisees on the left are most lightly bitten, and tonally present the one discordant note … The group of figures immediately below them, and to the right of them, are in the same style but have been partly redrawn in drypoint … the figure of the rich man … appears to have been drawn entirely in drypoint and burin in an extremely fine mesh of strokes … This is the first major work in which light and shadow were to attain such expressive power.” It is also worth noting that this was the first print which he made on Japanese paper which was being for the first time imported to the Netherlands – less absorbent and less coarse fibred than European papers, Japanese papers were ideal for registering every nuance in tone in impressions which Rembrandt painted with printer’s ink on the copper plate. Rembrandt’s The landscape with three trees, 1643, is the largest and most ambitious of the master’s landscapes (22 x 28 cm), where the dramatic chiaroscuro which he had developed for the interior religious scenes, he has applied to an outside setting and to nature. The title, one given to the print in the 18th century, somehow takes away from the full complexity of the composition. Although the scene may be set within the recognisable countryside outside of Amsterdam, it is more to do with the dramatic grandeur of nature. Here indicated by the mobility of light as the towering clouds in the distance seem to be drawing up water from earth, with visible streaks of rain, something which had never been attempted earlier in printmaking. Although it is the landscape which dominates all, it is nevertheless an inhabited landscape which the viewer will explore – like in the lower right, in the gap in the shrubbery are two lovers; on the left, on the edge of the foreground body of water are a fisherman and his wife; in the dale beyond the three trees is a cottage, while on the crest on the horizon is a wagon filled with travellers, on the far right is a seated draughtsman sketching the landscape. Cattle and herders can also be made out, as well as the outlines of a great city, but all reduced to insignificance by the grand landscape and the huge sky above it. Rembrandt here employs etching, drypoint and engraving and gives the landscape the dignity usually reserved for narrative history paintings. Rembrandt’s culmination as a printmaker is generally associated with a very large drypoint plate, Christ crucified (Three crosses) on which he worked from 1653 (first state) to 1660 (final state) measuring 39 x 45 cm. As art historians have pointed out “The Christ crucified involves one of the most radical revisions of a plate in the history of printmaking” The first state appears to illustrate the passage in Luke 23: 44-48 “And it was about the sixth hour, and there was darkness all over the earth until the ninth hour. And the sun was darkened, and the veil of the temple was rent in the midst. And Jesus had cried with a loud voice, he said, Father, into thy hands I commend my spirit: and having said thus, he gave up the ghost. Now when the centurion saw what was done, he glorified God, saying, Certainly this was a righteous man. And all the people who came together to that sight, beholding the things which were done, smote their breasts and returned”. In the first state there is clarity of detail, we see Christ and the crucified thieves, the followers of Christ like the Magdalene who embraces Christ’s feet, the swooning Mary, His mother, and the kneeling centurion, while in the bottom right-hand corner is a pool of darkness, alluding to the entombment of the body of Christ. In the fourth state the darkness has the full power, it is a scene of chaos and confusion as the darkness seems to stream from above. The moment which Rembrandt has chosen is that of the “darkness over all the land”. On the right-hand-side, a hail of deeply gouged drypoint marks threaten to obliterate Christ’s followers and the thief on the cross is almost totally swallowed up by the darkness. Figures have been scraped and radically altered, on the left a man reins a rearing horse, while on the right John flings out his arms in despair. A departing figure in the right foreground plunges into darkness and a stately mounted centurion holding a lance has been added. All is cast into shadow with the brightest spot in the composition being Christ’s halo. The figure of Christ has been redrawn, but he is the only one with what one may term a sculptural definition. It could be as Christopher White suggests that Rembrandt has now altered the interpretation of the scene to illustrate the episode narrated by the Evangelists Mark and Matthew “Now from the sixth hour there was darkness over all the land unto the ninth hour. And about the ninth hour Jesus cried with a loud voice saying … My God, my God! Why hast thou forsaken me?” In Christ presented to the people 1655, the revisions may appear to be less radical in the eight states of the print. Iconographically, it is an unusual image where Pilate presents Christ to the people who egged on by the Jewish priest cry “Crucify him!” Watching on from the top left-hand corner is an elegantly dressed woman, whose identity remains unclear, while the man of sorrows is presented on a platform for public abuse. Rembrandt largely changed the nature of the art medium, etching was no longer thought of as being in the service of another medium, it became an art form in its own right with infinite flexibility and creative originality. Rembrandt demonstrated for the first time that there were things which you do in etching which you could not attempt in any other medium. It was a unique challenge which was not again taken up until the modern era and artists as different as Whistler, Picasso, Matisse and Baldessin, could all turn back and call Rembrandt their teacher. Exhibition:

Rembrandt: True to Life NGV International, St Kilda Road | 2 June – 10 September 2023 |

2 Comments

Carmel O'Connor

12/6/2023 11:11:37

Dear Sasha Grishin,

Reply

Sasha Grishin

12/6/2023 11:17:58

Carmel - it is the same plate that Rembrandt has reworked. He did this frequently in his etchings

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

GRISHIN'S ART BLOG

Sasha Grishin AM, FAHA is the author of more than 25 books on art, including Australian Art: A History, and has served as the art critic for The Canberra Times for forty years. He is an Emeritus Professor at the Australian National University, Canberra; Guest Curator at the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne; and Honorary Principal Fellow, Faculty of Arts, at the University of Melbourne. Archives

June 2024

Categories

Keep up-to-date with Sasha Grishin's blog with the RSS feed.

RSS offers ease of access and ensures your privacy, as you do not need to subscribe with an email address. Click here to download a free feed reader |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed